4 Objects Galileo Discovered with His Telescope that You Can See with Binoculars

One of Galileo’s major contributions to science was his unprecedented use of telescopes for astronomy. In 1609, the telescope had only just been invented in the Netherlands, and Galileo used the design to make his own. Today, you can see much of what Galileo saw for the first time with a good pair of binoculars, a tripod, and a clear sky.

Here are a few to put to the test when you want to feel like an astronomical pioneer. To find their exact location for your time and place, we recommend using an astronomy app or site like The Sky Live or Sky Safari.

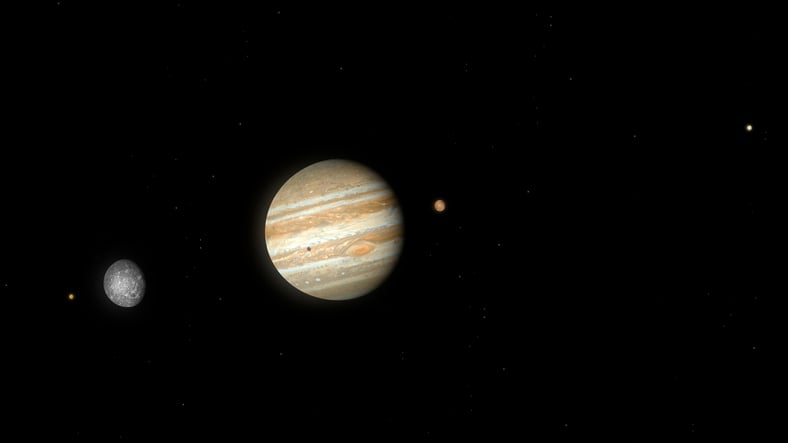

1. The moons of Jupiter

Before Galileo, humanity didn’t know that other planets had moons. The common belief was that everything in the universe revolved around the Earth. But Galileo saw four “stars” near Jupiter that orbited it instead.

Those four moons - Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto - are now called the Galilean Moons in his honour, and they continue to fascinate scientists to this day. Europa, for example, likely has an ocean beneath its icy crust and is one of the Solar System’s most likely spots for extraterrestrial life. Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System and is even bigger than Mercury. Callisto is one of the oldest objects in our Solar System and its most heavily cratered object. Finally, Io is the most geologically active object in the Solar System with over 400 volcanoes.

You can easily see all four Galilean moons with a pair of binoculars on a clear evening. You can even chart their movements around Jupiter over a few nights, just like Galileo. When looking at Jupiter, their order from closest to furthest is Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

2. Moon craters

Before Galileo, most scientists thought every object in the sky was a perfectly smooth sphere in line with Aristotle’s theories of the cosmos, the Moon included. There doesn’t appear to be a consensus on why the Moon had discolorations if it was perfectly smooth. Popular theories included that it’s proximity to Earth corrupted the light it emitted or that it was reflecting the Earth’s oceans and continents.

When Galileo started looking at the Moon, he noticed that it wasn’t smooth at all: it had craters and mountains and other features like the Earth. When he looked closely at the line between the dark and light sides (called the lunar terminator), he saw that it was uneven, suggesting these features were casting shadows. This challenged the dominant thought at the time and was another proof that the universe was much different than we thought.

Today, you can see many of the geological features that Galileo saw on our Moon. Plus, you can see different parts during different phases. During the first quarter, for example, you can easily see the shadows Galileo saw on the terminator line. As more of the Moon’s surface is illuminated from the Sun during the full moon, you can see famous features like the Sea of Tranquility and its many craters on the outer rim of visibility.

3. Stars in the Milky Way galaxy

The Milky Way has always been in the night sky, but people didn’t always know what it was. Many Europeans thought it might be some sort of cloud in space. Islamic astronomers theorized that it was a sea of stars too close together to separate out with the naked eye. Galileo, however, was the first person to see individual stars in the Milky Way. And you can, too, with a good pair of binoculars. It’s a chance to recognize the vastness of our own galaxy, which is estimated to have between 100 and 400 billion stars.

When you look at the Milk Way, you’re looking at the dense core of stars near its centre. This is because we’re further out on one of the arms that make up the galaxy’s spiral shape. And at the centre of the galaxy is the black hole SgrA*, which was famously photographed by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2022.

4. The Phases of Venus

Seeing the phases of Venus will take more powerful binoculars and some caution. Since our solar neighbour sits close to the Sun in the sky, you should instead look at it just before sunrise or just after sunset and when it is far away from the Sun in the sky. Never look at Venus when the Sun is out as it could damage your eyes.

To the naked eye, Venus only has extreme crescent phases. But with some help, you can see that it has phases just like the Moon. When Galileo saw this for the first time, it challenged the prevalent idea that the planets spun in little circles as they orbited the Earth, called “epicycles.” But if Venus had phases like the Moon, it had to go around the Sun at some point, which meant other objects probably went around the Sun as well.

Watching Venus can be tricky since it becomes difficult to see for long stretches throughout the year. Here’s a quick guide to the best times to look at Venus in 2025:

- February 1: Evening planet, visible soon after sunset.

- March 1-15: Evening planet, sets over 3 hours after sunset.

- April 25: Morning planet, rises 70 mins before sunrise. Forms a small triangle with Saturn and Neptune.

- June 1: Morning planet. Venus at greatest western elongation (morning).

- September 1: Morning planet rising 3 hours before the Sun.

- September 19: Venus moves behind the Moon for a few hours.

- October 1: Morning planet, rising 2 hours and 15 minutes before sunrise.

- End of October: Venus becomes increasingly difficult to see for the rest of the year.

If you would like to learn more about Galileo and his many discoveries, check out the Galileo exhibit happening at Perimeter Institute this February. Filled with replica artifacts and documents from Galileo’s life and time, it’s a journey through history and a look at how we started to change our perspective on our place in the cosmos.

À propos de l’IP

L'Institut Périmètre est le plus grand centre de recherche en physique théorique au monde. Fondé en 1999, cet institut indépendant vise à favoriser les percées dans la compréhension fondamentale de notre univers, des plus infimes particules au cosmos tout entier. Les recherches effectuées à l’Institut Périmètre reposent sur l'idée que la science fondamentale fait progresser le savoir humain et catalyse l'innovation, et que la physique théorique d'aujourd'hui est la technologie de demain. Situé dans la région de Waterloo, cet établissement sans but lucratif met de l'avant un partenariat public-privé unique en son genre avec entre autres les gouvernements de l'Ontario et du Canada. Il facilite la recherche de pointe, forme la prochaine génération de pionniers de la science et communique le pouvoir de la physique grâce à des programmes primés d'éducation et de vulgarisation.