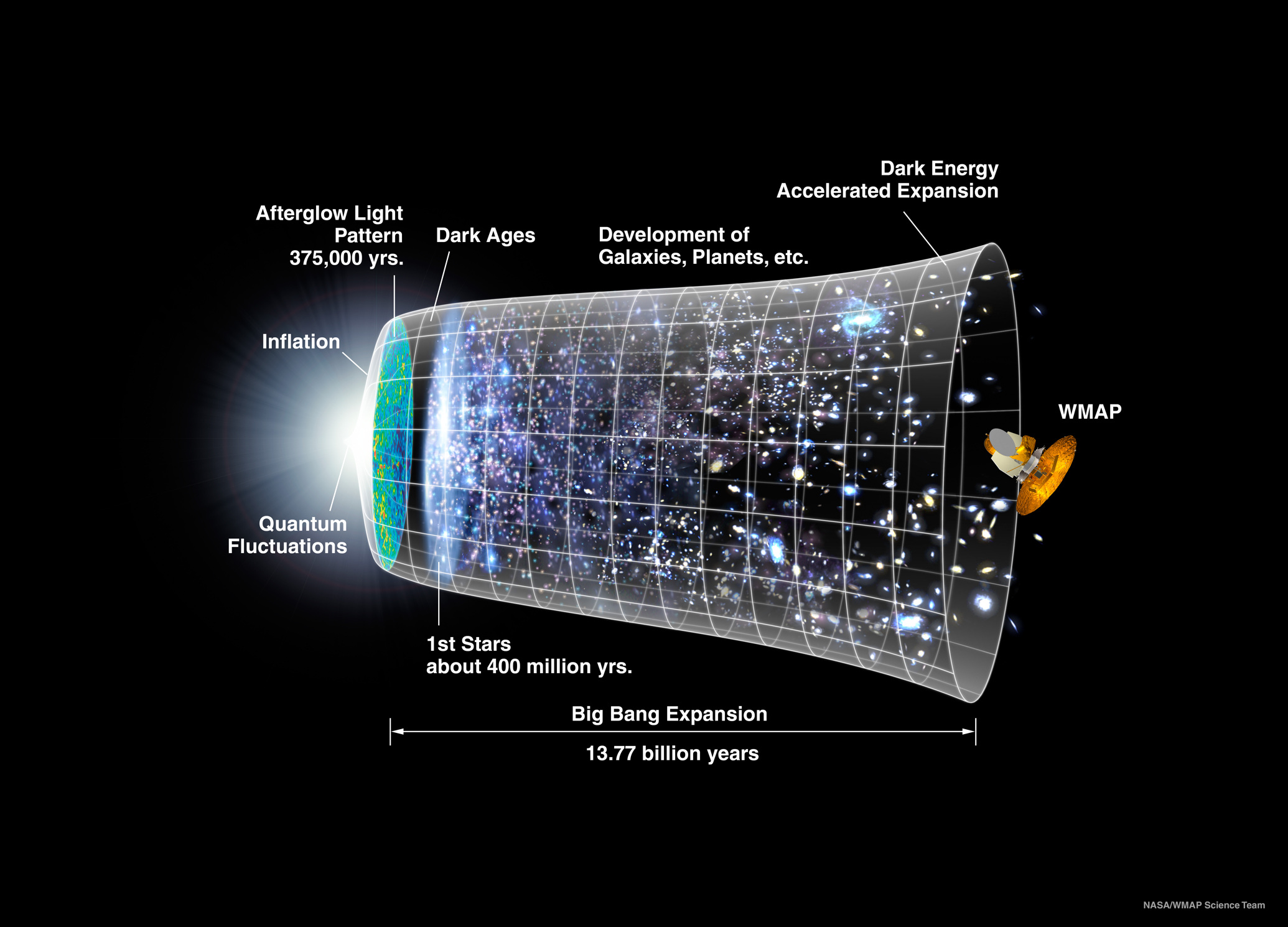

What is the universe made of? How did it begin? Will it ever end? In recent decades, physicists have produced dramatic new answers to these ancient cosmological questions. They're also exploring new mysteries about the nature of dark matter and dark energy, the story of the big bang singularity, and the shape and structure of spacetime itself.

Over the past few decades, a flood of astronomical data has led cosmologists to a strikingly simple picture of the universe. Yet there are big gaps between what we see and what we know, and this has created a raft of questions for modern cosmologists.

From Einstein's theory of general relativity (our modern theory of gravity) we know that spacetime may be curved in all manner of strange ways. Yet we observe that our own universe, in its infancy, was remarkably simple: almost perfectly flat, homogeneous (the same at all positions), and isotropic (the same in all directions).

The universe was filled with tiny density ripples, which grew over time to form the complex web of stars, galaxies, and clusters that surround us today. But again, at early times, these ripples seem to have been extremely simple (characterized, technically, by almost perfect adiabaticity, gaussianity, and a pure power-law spectrum). Why did the early universe start in such a simple state? Why did it start in this particular state?

Einstein's theory also seems to predict that, if we could look even further back in time, we would encounter a "singularity" (commonly known as the big bang) where the temperature and energy density of the cosmos become infinite. But Einstein's theory is classical, and cannot be trusted too close to such a singularity. That leaves cosmologists with nagging questions: did we really have such a singularity in our past? If so, did the universe begin there, and how? If not, what is the correct mathematical description of the universe at such early times?

Another question facing modern cosmologists is how the universe evolved from its simple initial state to the more complex cosmos we see around us today. Observations have led to a simple model — the so-called "LambdaCDM" model — which (apart from some possible, though still controversial, exceptions) does a good job of accounting for the available data, but only at the cost of introducing two mysterious new substances — dark matter and dark energy.

We know very little about these substances, and so far have only been able to detect them via their gravitational effects on cosmological length scales. We do not know, as yet, what these substances are, nor how they relate to the "ordinary matter" that makes up stars, planets, and people. Could dark matter and dark energy be a clue that Einstein's theory of gravity — which is so successful on Solar System scales — must be replaced by a better theory in order to accurately describe the universe on cosmological scales?

The cosmology group at PI works on developing new theoretical ideas and mathematical models aimed at addressing these various questions, and also on developing new ways to test these ideas observationally and experimentally. Modern cosmology is awash in high-quality astronomical data, and an important part of the cosmology research effort at PI involves inventing new and clever ways to analyze these data sets in order to test our mathematical theories, to beat back the boundaries of our ignorance, and hopefully discover new and unexpected phenomena hiding there, waiting to be unveiled by the right question and the right analysis.

Cosmology researchers

-

-

-

-

Kendrick Smith

Research Faculty

Perimeter Research Chair

The Daniel Family James Peebles Chair in Theoretical PhysicsCosmology -

-

-

Ghazal Geshnizjani

Teaching Faculty

Academic Staff

Training, Educational Outreach and Scientific Programs

Teaching FacultyCosmology -

Neil Turok

Perimeter Research Chair

Perimeter Research Chair (Visiting)

Carlo Fidani Roger Penrose Distinguished Visiting Research Chair in Theoretical PhysicsCosmology -

Kendrick Smith

Research Faculty

Perimeter Research Chair

The Daniel Family James Peebles Chair in Theoretical PhysicsCosmology