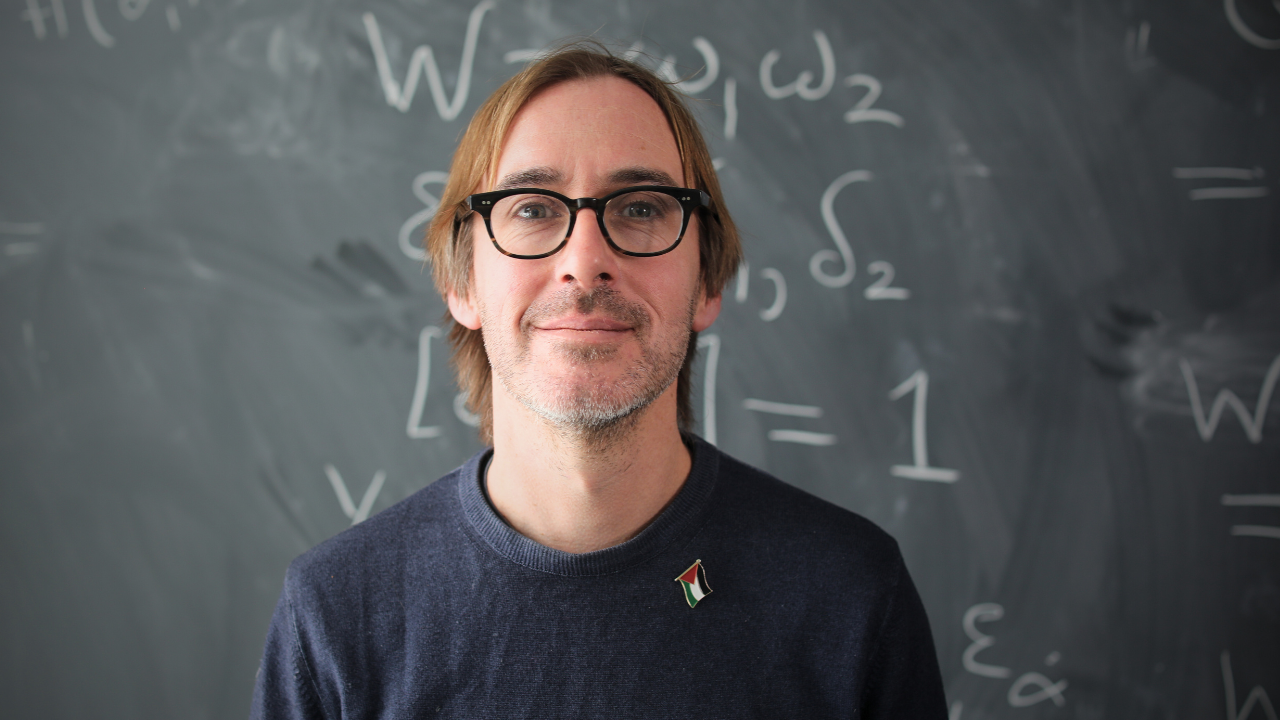

When Kevin Costello was 10, growing up in the small Irish fishing village of Kinsale, he knew exactly what he wanted to be when he grew up.

“I wanted to be Jimi Hendrix,” says Costello. “As you can see, that didn’t happen.”

Although rock stardom was not in the cards for the soft-spoken Costello, he found a niche that suited both his personality and his voracious curiosity: theoretical physics.

Costello’s childhood daydreams of shredding guitar solos for rabid fans gradually gave way to complex mathematical puzzles, which he first discovered in the back pages of his father’s stacks of Scientific American magazines dating back to the 1950s. His older brother helped him figure out how to code the Mandelbrot set, an infinitely complex shape created by repeatedly squaring numbers and adding a starting value.

Now, as a faculty member at Perimeter Institute, he spends his days immersed in the equations and formulas of mathematical physics, aiming to tease out new ways of understanding space, time, matter and energy.

Costello joined Perimeter in 2013 as the Krembil Foundation William Rowan Hamilton Chair, named after the Irish mathematical physicist whose groundbreaking work in quaternions helped shape modern physics and mathematics – much like Costello’s own contributions to quantum field theory.

Costello’s recruitment to Perimeter was vital in expanding the pursuit of mathematical physics at the Institute. He was recruited at the same time as Davide Gaiotto, who holds the Krembil Foundation Galileo Galilei Chair in Theoretical Physics, and the two have made significant contributions – together and individually – to mathematical approaches to quantum field theory.

Together, for example, Costello and Gaiotto developed twisted holography, which provides a more concrete way to study quantum gravity.

"Holography is a popular idea in physics, but the problem is that quantum gravity isn’t really well-defined,” explains Costello. “We created a simplified toy version where we could actually get our hands on it and make sharp statements.”

Twisted holography aims to simplify the complex ideas of the holographic principle, which suggests that all the information within a volume of space can be described by data on its boundary. It’s similar to how a hologram on a credit card works, but the mathematics involved is often very intricate.

To make these concepts more manageable, Costello and Gaiotto focus on specific "twisted" versions of physical theories. In this context, "twisting" refers to modifying a theory to highlight its most essential and simplified features, stripping away complexities that can obscure understanding. By applying this twisting process, they can study a more straightforward version of the holographic relationship, making it easier to explore and understand.

This approach not only provides clearer insights into the holographic principle but also uncovers new connections between different areas of physics and mathematics. By examining these simplified models, researchers can better examine fundamental structures underlying space and time.

It is complex and highly original research, requiring both collaboration across disciplines and intense solo contemplation – a mix Costello enjoys.

"Coming here, people were much more open to collaborating across disciplines. I learned so much talking to the physicists," he says.

"Sitting alone and doing calculations can be isolating, but bouncing ideas off colleagues is what makes it exciting."

When he’s not doing physics, Costello has found a way to connect with his childhood love of music; he plays viola in Perimeter Institute’s in-house orchestra with fellow researchers, students, and staff.

While playing viola in an orchestra isn’t exactly the same as shredding guitar solos like Jimi Hendrix, music provides a satisfying counterpoint to all the complex mathematics.

“Our string quartet played the theme from Jurassic Park,” he says. “That was fun.”

He says music, like mathematics, can be a satisfying solitary pursuit, but beautiful harmonies can emerge when people work together.

"The work I do is fun because of the collaboration,” he says. “You have some idea, you share it with somebody, and you develop it together. The really fun parts are the collaborations where Perimeter brings together people from all different areas."

À propos de l’IP

L'Institut Périmètre est le plus grand centre de recherche en physique théorique au monde. Fondé en 1999, cet institut indépendant vise à favoriser les percées dans la compréhension fondamentale de notre univers, des plus infimes particules au cosmos tout entier. Les recherches effectuées à l’Institut Périmètre reposent sur l'idée que la science fondamentale fait progresser le savoir humain et catalyse l'innovation, et que la physique théorique d'aujourd'hui est la technologie de demain. Situé dans la région de Waterloo, cet établissement sans but lucratif met de l'avant un partenariat public-privé unique en son genre avec entre autres les gouvernements de l'Ontario et du Canada. Il facilite la recherche de pointe, forme la prochaine génération de pionniers de la science et communique le pouvoir de la physique grâce à des programmes primés d'éducation et de vulgarisation.

Ceci pourrait vous intéresser