From the solar eclipse to a map of our universe 11 billion years in the making, it’s been an eventful year in the field. Researchers are evolving our understanding of long-established theories and accessing never-before-seen images of galaxies far, far away. They’re also doing some serious problem-solving, like how to successfully transport antimatter. Here are 17 physics stories that made headlines in 2024.

The Great Solar Eclipse of 2024

On April 8, 2024, all eyes were on the sky with a once-in-a-lifetime total solar eclipse. Across North America and Central America, humans in eclipse glasses could be seen gathered in groups, experiencing the wonder of this rare celestial event. A partial eclipse was visible across North America and Central America, with the path of totality visible from parts of Mexico, the United States, and Canada.

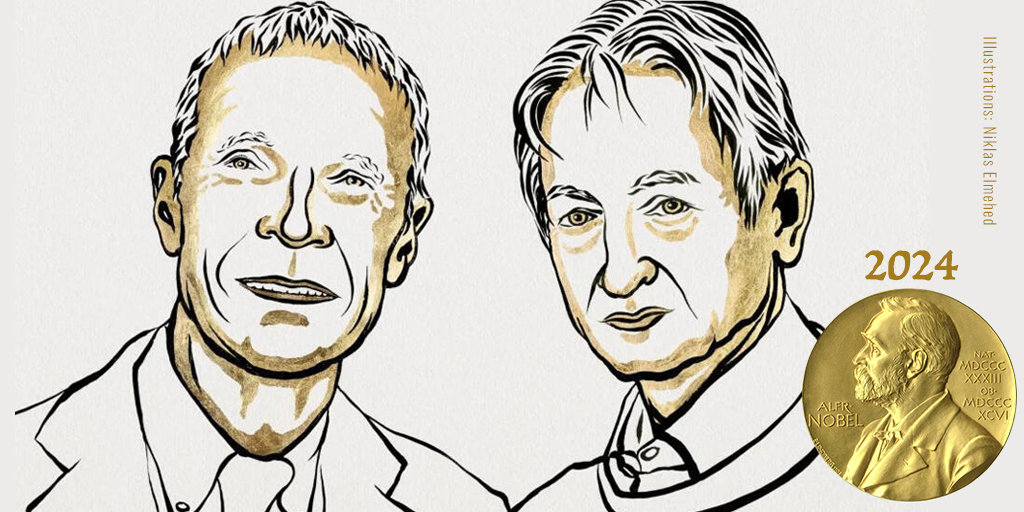

Toronto computer scientist received Nobel Prize in Physics

Canadian scientist Geoffrey Hinton, the widely regarded “godfather of AI,” was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics, a prize he shares with John Hopfield of Princeton University. Both scientists are pioneers in the field of machine learning and neural networks. Hinton’s work was acknowledged for the foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks, underlining the many innovative applications of physics tools for emerging technologies.

United Nations has declared 2025 the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology

2025 will officially be the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ). This year-long, worldwide initiative will “be observed through activities at all levels aimed at increasing public awareness of the importance of quantum science and applications.” The year 2025 was chosen in recognition of 100 years since the initial development of quantum mechanics.

New leadership for Perimeter

Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics welcomed a new Executive Director, Marcela Carena in 2024. Carena is the first woman to lead Perimeter, and she has previously held a post as a Distinguished Visiting Research Chair – the same position once held by Stephen Hawking – and has served as the Chair of Perimeter’s Scientific Advisory Committee since 2022. She takes the helm at an exciting time, as Perimeter celebrates its 25th anniversary in 2025.

Curious what Perimeter Institute got up to during 2024? Watch a year in review here.

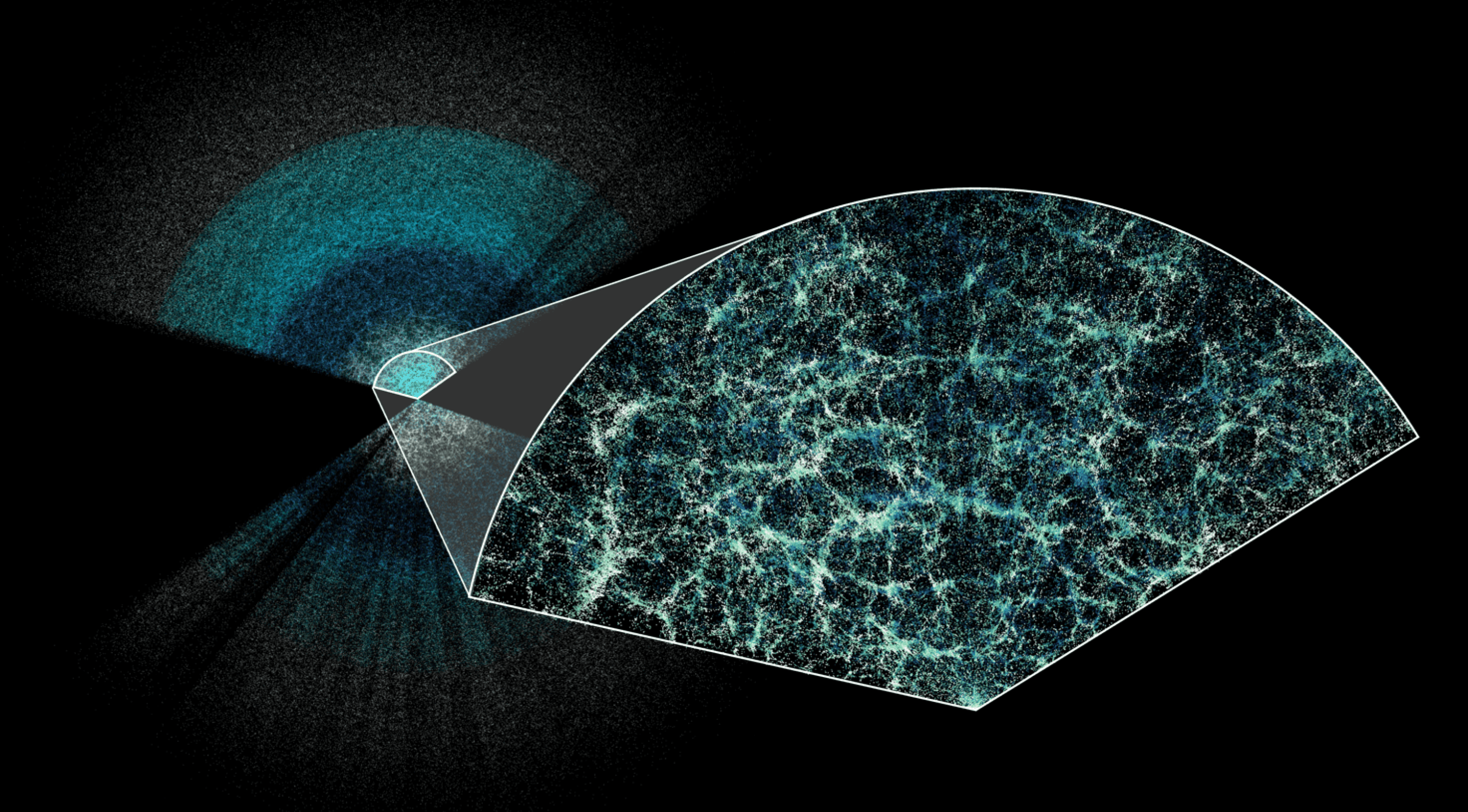

DESI looked waaay back – 11 billion years

Canadian scientists working with the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) participated in the collaboration’s first-year analysis of an exciting new three-dimensional map of the universe, providing never-seen-before details about our cosmological past. The collaboration has produced the largest 3D map of our universe to date that can see 11 billion years into the past, and help scientists understand how the universe has grown and evolved.

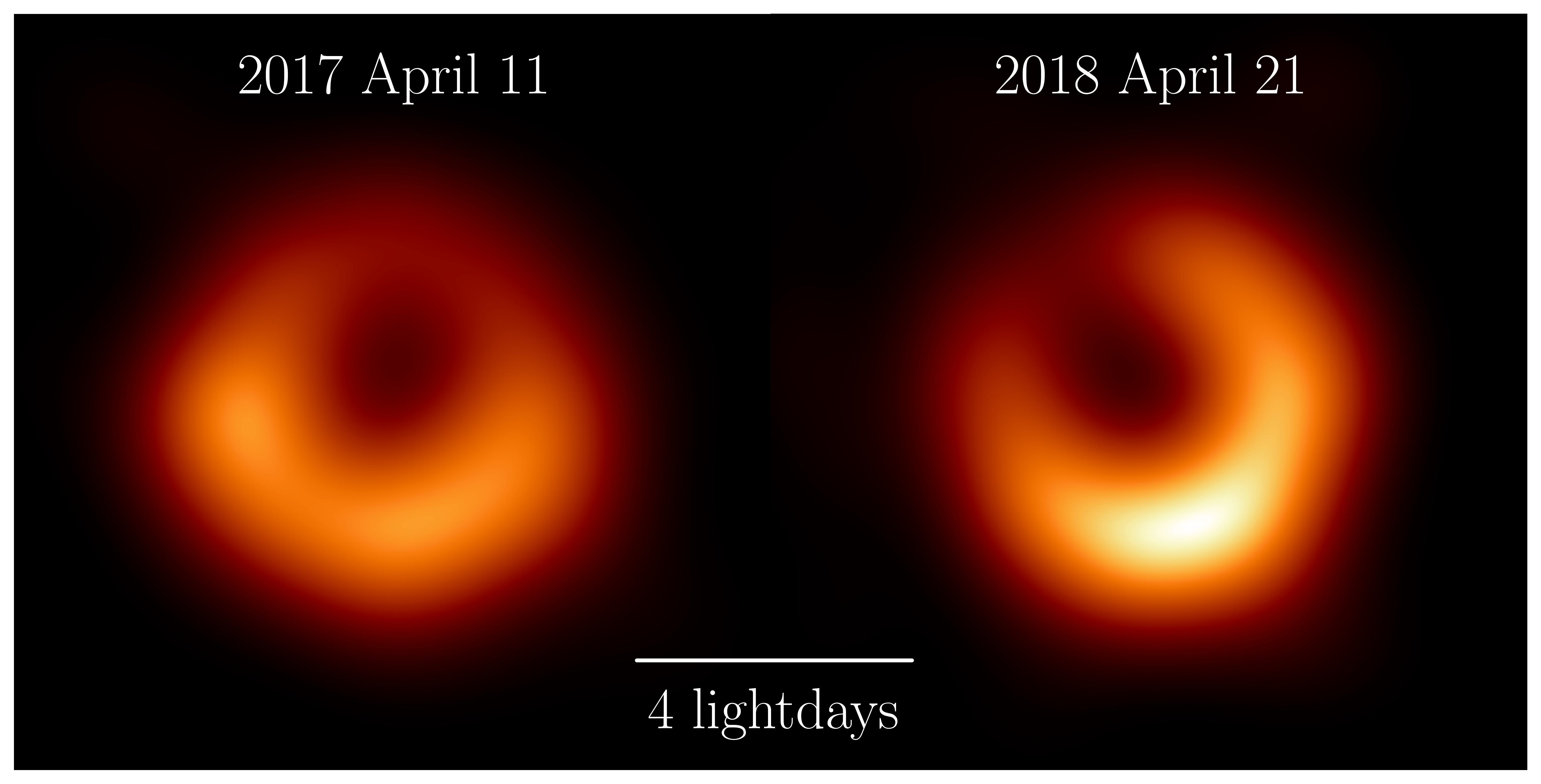

Event Horizon Telescope showed proof of persistent black hole shadow

In a 2024 paper published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration released new images of a supermassive black hole at the centre of the galaxy Messier 87. Data from observations taken in April 2018 are consistent with images from 2017, which revealed a bright circular ring, brighter in the southern part of the ring. The brightness peak of the ring has shifted by about 30º compared to the images from 2017, which is consistent with the researchers’ theoretical understanding of variability from turbulent material around black holes. Further analysis provides important insights into the geometry of the magnetic field and the nature of the plasma around the black hole.

Has the ‘Hubble Tension’ been resolved?

How fast the universe is expanding is hotly debated among astronomers. It’s a puzzle called the Hubble Tension that suggests the theoretical model of the cosmos might need some tweaking, because the rate of acceleration of the universe’ expansion appears to have been different during the early universe than in the late universe. In 2024, University of Chicago astronomer Wendy Freedman led a team that discovered new ways to measure the expansion rate using data from the James Webb Space Telescope. Her findings suggest the tension between the competing measurements of the Hubble constant might actually now be resolved. However, the debate, sometimes dramatically dubbed the ‘Crisis in Cosmology’ is expected to continue as more data becomes available in the coming years.

New images showed ‘Sombrero Galaxy’ is less hat-like than scientists thought

Hats off to NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope for capturing striking images of the Sombrero galaxy, named for initial images in which the galaxy resembled a broad-brimmed Mexican hat. Updated higher-resolution images of the galaxy – also known as Messier 104 – show the galaxy’s outer ring for the first time. Images show intricate clumps of dust that may indicate the presence of young star-forming regions.

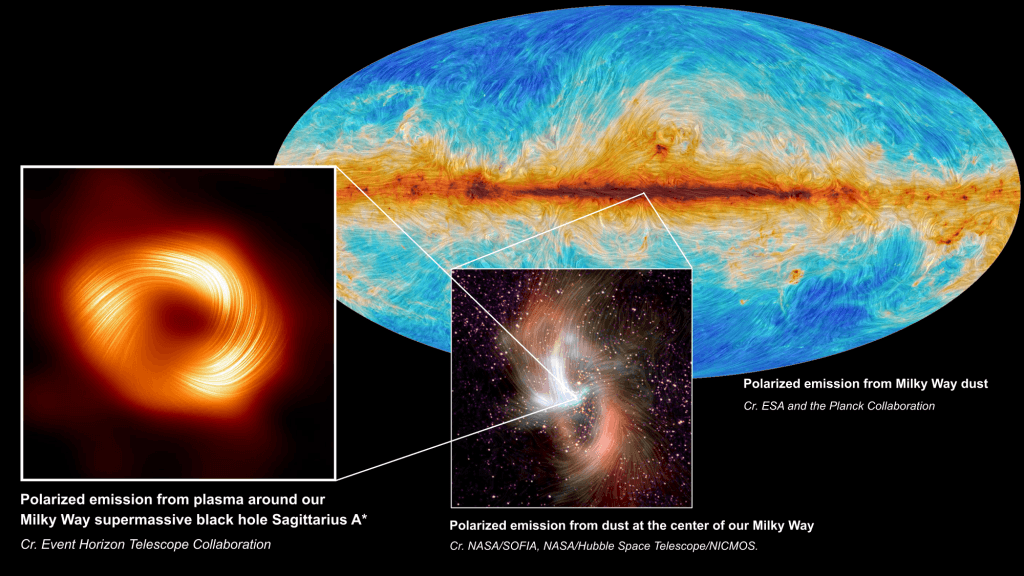

The Milky Way and its magnetic fields

There is a supermassive black hole at the heart of our galaxy, and in 2024 Perimeter researchers, alongside the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, helped capture never-before-seen images in unprecedented detail. The images of Sagittarius A* revealed the plasma ring and magnetic field lines that shape and organize it. It means researchers’ best theories about how supermassive black holes grow and evolve are on track, providing an empirical foundation for the science of galactic evolution and extreme gravity environments.

The first nuclear clock

What countdown would be complete without talk of timekeeping? Researchers in Colorado observed a signal they had been waiting on for 50 years, thorium-229 nuclei. The signal was the final piece of the puzzle needed to lead to the development of the world’s first nuclear clock, which would use nuclear energy levels to more precisely keep track of time.

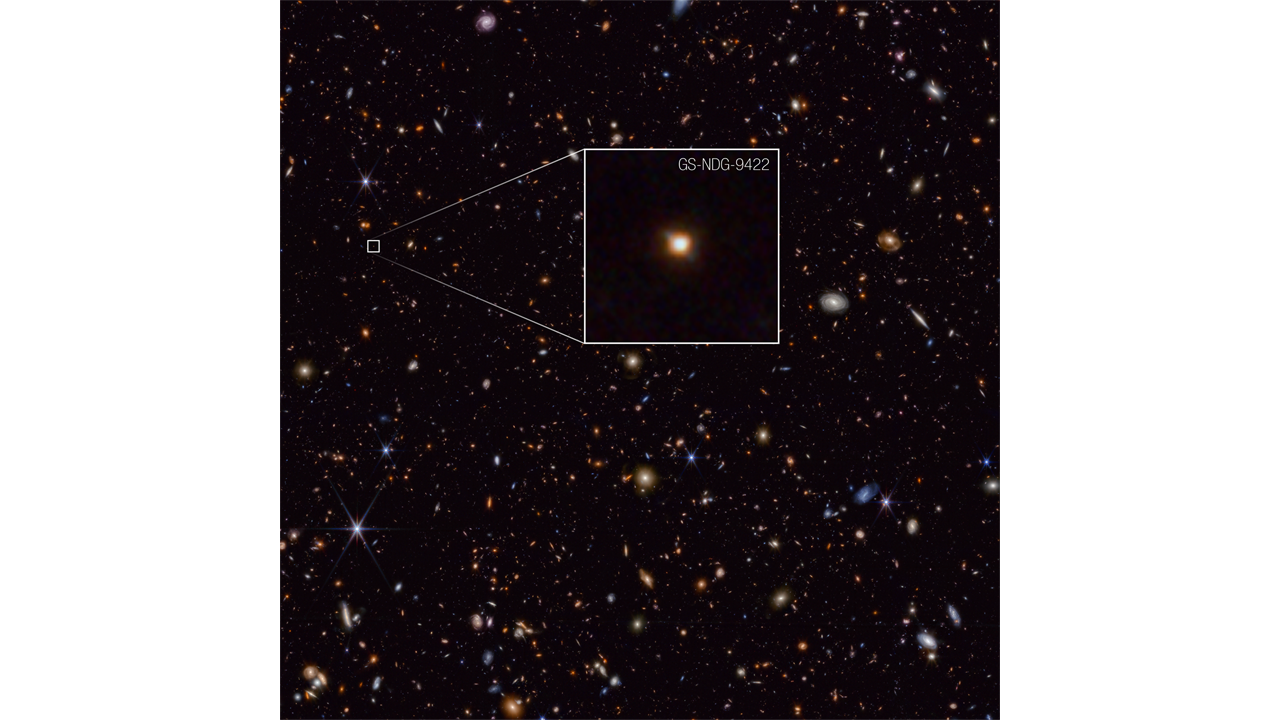

Galaxy 9422 was discovered one billion years after the big bang

Researchers working with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope may have discovered a totally new phenomenon in the early universe that will help them understand how the cosmic story began. In September, they announced a galaxy with an odd light signature, which they attribute to its gas outshining its stars. In the local universe, typical hot, massive stars have a temperature ranging between 70,000 to 90,000 degrees Fahrenheit (40,000 to 50,000 degrees Celsius). Found approximately one billion years after the big bang, Galaxy 9422 may be a missing-link phase of galactic evolution between the universe’s first stars and familiar, well-established galaxies.

ESA's Euclid released new views of the universe

In May, ESA’s Euclid space mission released five unprecedented new views of the universe. The new images – and scientific data – are part of Euclid’s Early Release Observations. The release targeted 17 astronomical objects, from nearby clouds of gas and dust to distant clusters of galaxies.

Remembering Peter Higgs

In April, Nobel-winning physicist Peter Higgs died at 94. Higgs was best known for proposing the existence of the Higgs boson, which is often referred to as the “God particle.” The Higgs boson is the fundamental particle associated with the Higgs field, a field that gives mass to other fundamental particles such as electrons and quarks. The Higgs boson was proposed in 1964 and discovered nearly 50 years later.

New quantum computer beat Google’s Sycamore machine

A new quantum computer, the H2-1, ran a simple quantum algorithm known as Random Circuit Sampling (RCS), and achieved a 100 times improvement over results that Google’s Sycamore machine achieved in 2019. The H2-1 is developed by quantum computing company Quantinuum and financial services firm JPMorgan Chase. The H2-1 is the industry’s first quantum computer with 56 trapped-ion qubits, and it runs at an estimated 30,000 times reduction in power consumption compared to classical supercomputers.

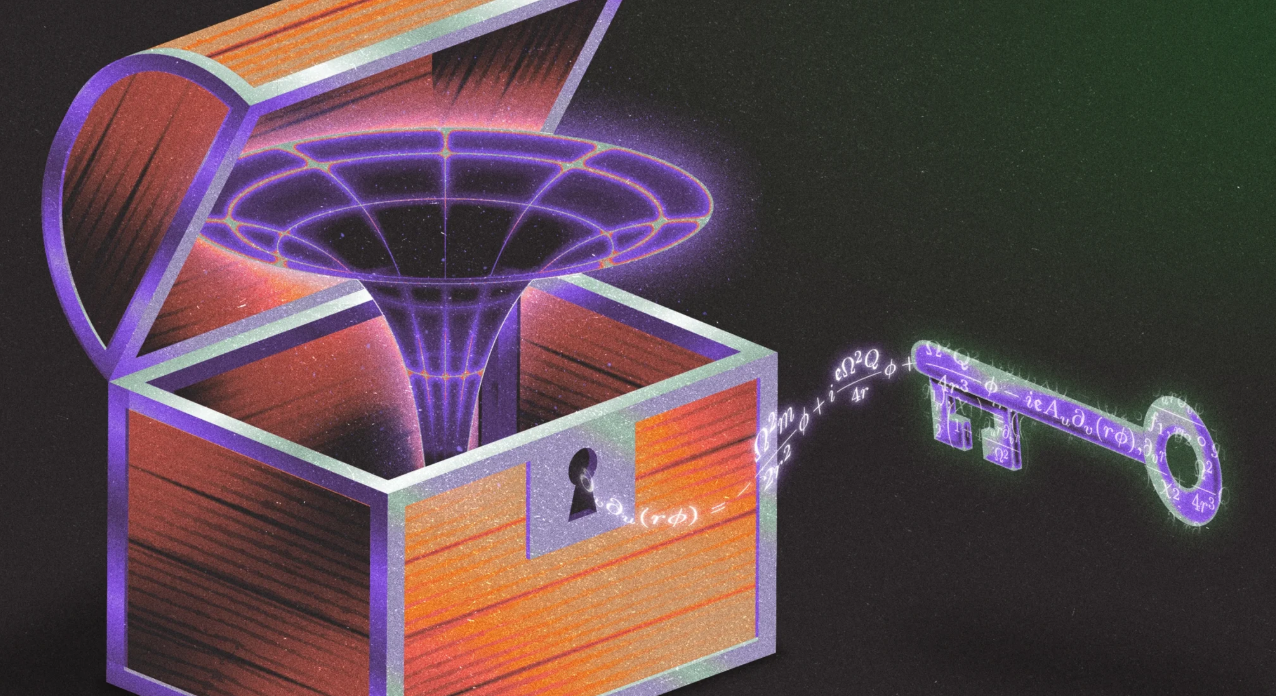

Mathematicians prove Hawking wrong about the most extreme black holes

In 1973, Stephen Hawking and colleagues argued that a special type of theoretical black hole called ‘extremals’ could not exist in the real universe. These oddball entities have no surface gravity at their event horizon, and seemed impossible. But this year, two mathematicians showed that there is no known law of physics that prevents the formation of extremals. Still, being mathematically feasible doesn’t mean they are real, and the jury is still out on whether they actually exist.

BASE experiment may lead to portable antimatter

Antimatter is a precious resource, and oh-so-delicate. The subatomic particles are so touchy that they can annihilate on contact with matter. Because they are so fragile, the European laboratory, CERN is currently the only place where antimatter particles can be trapped and studied. In November, scientists working on the BASE experiment successfully stored and transported a cloud of protons across CERN’s main site by truck. It’s a first step toward eventually creating an antiproton-delivery service from CERN to experiments located at other laboratories.

Quantum physics rules out black holes made of light

Black holes are believed to be formed by the collapse of giant stars. Einstein’s theory of relativity also predicted “kugelblitze,” black holes made entirely of high concentrations of light. Now, University of Waterloo scientists led by Álvaro Álvarez-Domínguez have proved it’s not possible to concentrate enough light to form a black hole. Their calculations are related to the Schwinger effect, a quantum physics phenomenon in which matter is created by a strong electric field. The particles and antiparticles would hurtle away from the light and prevent a black hole from condensing, they say.

Stay Ahead of the Curve in Physics

Want to be the first to know about groundbreaking discoveries, cosmic mysteries, and the stories shaping our understanding of the universe? Subscribe to Perimeter's newsletter for monthly updates on cutting-edge physics research, expert insights, and exclusive content from the world’s leading thinkers in theoretical physics.

About PI

Perimeter Institute is the world’s largest research hub devoted to theoretical physics. The independent Institute was founded in 1999 to foster breakthroughs in the fundamental understanding of our universe, from the smallest particles to the entire cosmos. Research at Perimeter is motivated by the understanding that fundamental science advances human knowledge and catalyzes innovation, and that today’s theoretical physics is tomorrow’s technology. Located in the Region of Waterloo, the not-for-profit Institute is a unique public-private endeavour, including the Governments of Ontario and Canada, that enables cutting-edge research, trains the next generation of scientific pioneers, and shares the power of physics through award-winning educational outreach and public engagement.