It has been two and a half years since Encieh Erfani first realized she couldn’t go home. She was three weeks into a three-month fellowship in Mexico, when distressing news came from her home country of Iran. A young woman named Mahsa Amini died after being arrested by Iran’s Gasht-e-Ershad, known as the “morality police,” for wearing an improper hijab. The “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests started the same day. Erfani was an Assistant Professor at the prestigious Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences in Zanjan, Iran. There are 86,000 faculty members across Iran, and universities are controlled by a totalitarian regime, with intelligence offices located directly in universities. Erfani thought she would be one of many faculty members to resign in solidarity with the protests. She decided it would be cleaner to do it before the semester officially started.

“I wrote a really short email, and in the last sentence I criticized the regime, and said their hands were dirty with the blood of my people,” Erfani says. She hovered over that last sentence for more than an hour before hitting send. “I was thinking about what could happen to my family. I didn’t realize I would be the first faculty member to resign. And of course, I never imagined it would lead to exile.”

Since Erfani sent her email early in the morning of a holiday, she assumed it would be hours or days before someone read it. She was prepared to accept the consequences of no longer having a job, and she knew she would probably face investigation when she returned in two months.

Within hours, intelligence officers had contacted and intimidated Erfani’s family. Then she began to receive messages from friends and colleagues who were working abroad, asking if she was safe. Erfani’s resignation letter had been shared far beyond the small group of physics students and colleagues she sent it to. Erfani, who didn’t even have a Twitter account, was trending on the platform. Her opposition to the regime had gone viral, and she was blacklisted.

Coming to Perimeter

Erfani has no record of employment. The regime removed her access to email and the portal where her documents are stored. These documents are essential for visa and job applications.

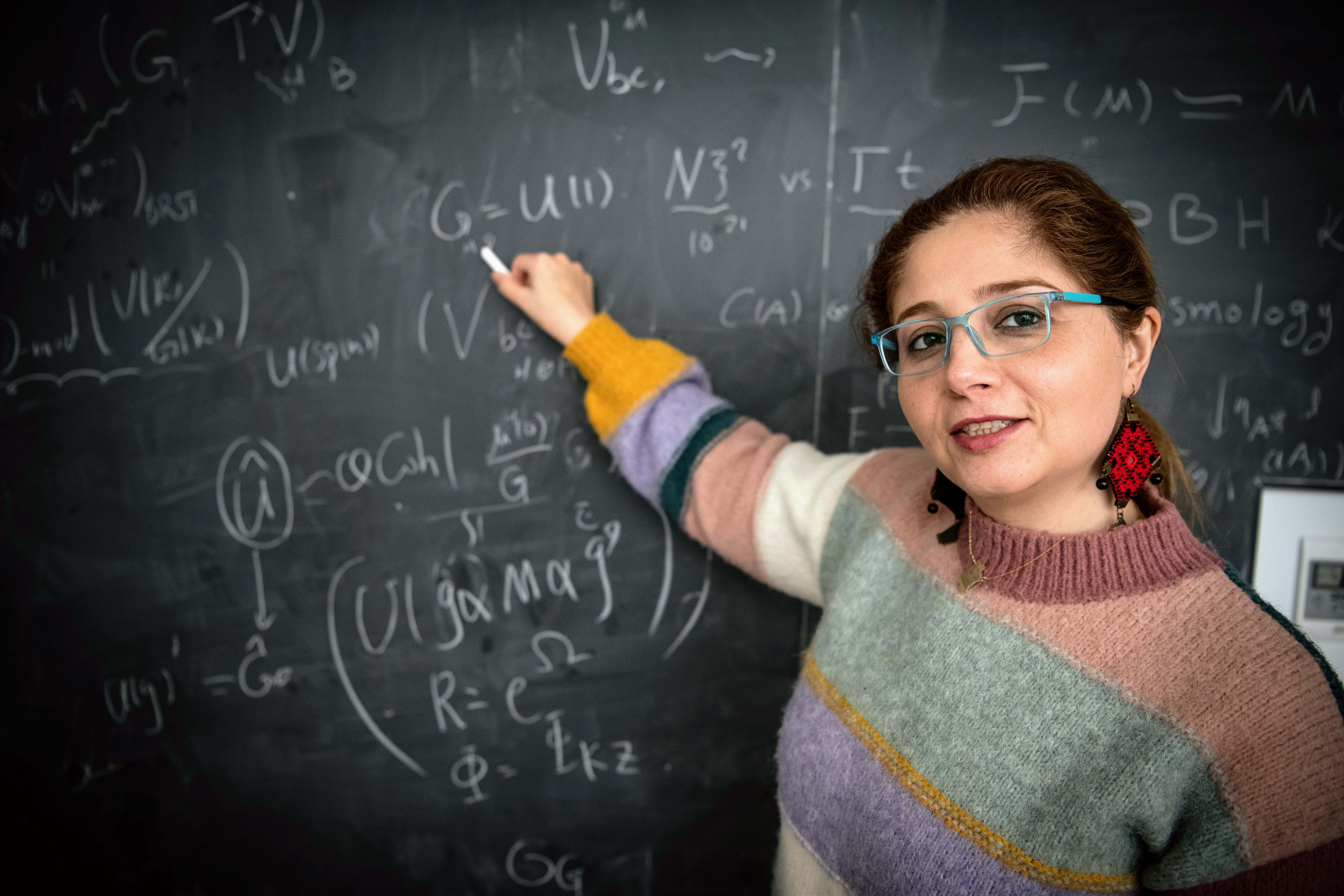

In February 2025, Erfani joined Perimeter’s Cosmology group for a one-year term. It took nearly eight months to get approved for a visa to enter Canada.

As a cosmologist, Erfani’s work is focused on primordial black holes, which she says has become more of a hot topic in the 10 years since gravitational waves were detected. She also works on inflationary models, one of the mechanisms of forming primordial black holes.

“That’s a part of my job that I really love, and it excites me still,” she says. “If my country was free, I would be an ordinary researcher, conducting research, going to conferences, and talking with friends about science.”

The path to cosmology

Erfani fell in love with astronomy as a child, watching the night sky at her grandparents’ home with her cousins. When she looked through a telescope at a public event, she saw Saturn for the first time.

“Even these days, I still get excited when I look at Saturn,” she says.

Throughout her career, she has been active in astronomy groups and outreach activities for the general public. She started an astronomy club that made it possible for women to stargaze safely together. She even convinced the mayor of her city to host astronomy events in a large city park.

In 2007, she was awarded a Postgraduate Diploma Scholarship in High Energy Physics from the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy. She completed her PhD in the Physics Department of Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn in Germany.

Erfani says she comes from a traditional Iranian family, and she is the first to attend university. Her academic interests were challenging for her family, especially when they required her to be out late at night after attending meetings and events. She says her mother often encouraged her to be mindful of what it meant to be a young woman in Iran. Erfani says although she always wore a scarf in public, she sometimes removed it while driving home, an act that prompted text messages from morality police who claimed she had been caught on camera.

As a faculty member, Erfani often worked to promote and encouraged women in science, although she was often met with opposition by colleagues and labelled a feminist – a charged term in Iran. During COVID, she tried to host an online workshop with the American Physical Society about diversity, equity and inclusion. She was unable to obtain the five faculty signatures and a letter of support from her department chair the society required to make the workshop happen.

Humanity in the sciences

In February 2025, Erfani received the biggest award of her career to date. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) named her as the recipient as the AAAS Award for Scientific Freedom and Responsibility. She was unable to attend the award ceremony in Boston because it would have required a visa.

The award recognized Erfani’s advocacy for at-risk students and scholars. In 2018, she organized the first physics workshop at Kabul University, which led to the establishment of a scholarship to enable Afghan students to pursue master’s degrees in Iran. In 2021, she collaborated with the “Science in Exile” initiative to support at-risk displaced scholars. Most recently, she has co-founded the International Community of Iranian Academics (ICOIA) that tracks the latest statistics on students killed, detained, and imprisoned in Iran.

Erfani notes the scientific community has a profound history of protecting displaced scientists, especially during the Second World War. Einstein, Meitner, and Schrödinger famously reached safety abroad with help from colleagues.

“I think about where physics would be if we didn’t help these people,” she says. “This is the humanity in sciences. I never trained to become political or a social activist, but sometimes life forces you to be one.”

Erfani has developed an interest and expertise in scientific diplomacy, and she has taken as many courses as she could find on the topic. She argues many of the fellowships that are available to support scholars focus too heavily on scientific background, number of publications, and visibility in the scientific community. For many at-risk scientists, this can be a barrier to accessing new opportunities in a safe environment.

Prior to arriving at Perimeter, she worked as a researcher in Mainz University in Germany. Erfani says Europe was a temporary solution. As an Iranian, she had no health care, and she was unable to access even basic services like a bank account. She was paid in cash, and simple tasks like booking travel or paying for documents sometimes took weeks of negotiation. The paper trail associated with payments linked to Erfani’s name came with personal risk to her helpers. She once took a 20-hour bus ride between countries because she was reluctant to ask a friend to book her a plane ticket for the short flight using their credit card.

“It’s not just me, or women, or the Middle East,” she says. “I have friends from Cuba, Russia, Belarus, and other places where political restrictions affect the lives of scientists.”

Life in Canada

Erfani’s Canadian visa was approved with only weeks to spare before her fellowship offer expired. For now, she is focusing on her research and building a life in Canada, perhaps in the field of scientific diplomacy.

“I stand against a dictator, but the shadow of the dictator still follows me when I apply for a visa or when people see my nationality. It doesn’t matter to them that I stand against the regime,” she says.

Erfani’s advocacy work is supported by many Iranians living abroad who are not listed on the ICOIA’s website for safety reasons. Few Iranians like and share her LinkedIn posts, but she knows from private messages that many follow and support her activities.

“Another important part of the work we are doing with the ICOIA is to build the community of accomplished Iranian scientists,” Erfani says. “We know the regime will collapse one day, and we will need our scientists when it’s time to rebuild.”

À propos de l’IP

L'Institut Périmètre est le plus grand centre de recherche en physique théorique au monde. Fondé en 1999, cet institut indépendant vise à favoriser les percées dans la compréhension fondamentale de notre univers, des plus infimes particules au cosmos tout entier. Les recherches effectuées à l’Institut Périmètre reposent sur l'idée que la science fondamentale fait progresser le savoir humain et catalyse l'innovation, et que la physique théorique d'aujourd'hui est la technologie de demain. Situé dans la région de Waterloo, cet établissement sans but lucratif met de l'avant un partenariat public-privé unique en son genre avec entre autres les gouvernements de l'Ontario et du Canada. Il facilite la recherche de pointe, forme la prochaine génération de pionniers de la science et communique le pouvoir de la physique grâce à des programmes primés d'éducation et de vulgarisation.