Call it a glass obstacle course. Call it a mountain made from many molehills. Call it a gender gap that will take more than 250 years to correct at the current rate of progress. The lack of diversity in physics faculties can be described in many ways, and Rowan Thomson will say them all out loud if they motivate people to bring about change.

“Diversity in physics is an ongoing challenge, but it’s not often openly discussed,” she said to a group of faculty, staff, and students at a recent workshop for Perimeter Institute. “You need to be part of the discussion, but even more important, you have to take action.”

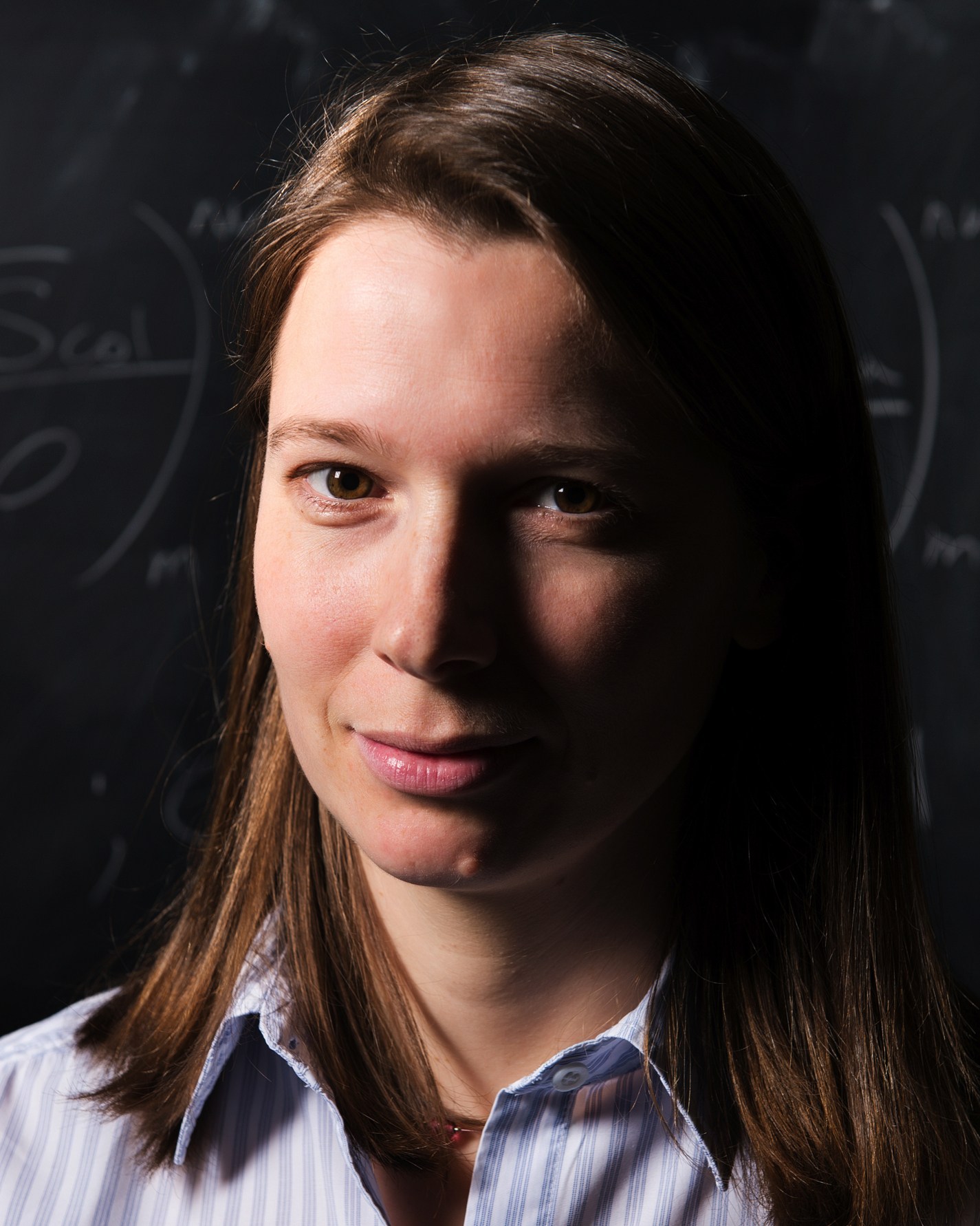

Thomson, a Perimeter alumna, is now Carleton University’s Assistant Dean for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. She studied string theory at Perimeter, but at Carleton, she researches how radiation interacts with matter – a physics question directly related to cancer therapies. She said she experienced systemic diversity issues personally long before she found a way to address them in a professional capacity.

“The first day of my summer job in 2001 as an undergrad working at the National Research Council, I remember going into the lunchroom, sitting down to eat, and thinking, ‘Oh my goodness, all the scientists are men,’” she said. “There were no senior women physicists I could model myself after.”

She still questions whether the uncomfortableness of that imbalance later contributed to her changing fields.

“Women talk about ‘the sense of not belonging.’ I wouldn’t have used those words for me,” she said. “But I switched fields because I didn’t see it working out the way I wanted in theoretical physics. I did a postdoc in medical physics instead.”

Now, in addition to her radiation research, she also studies the gender gap in physics and gives workshops on how to solve the problem. ‘The glass obstacle course’ refers to all the hurdles that only women face in pursuit of a career in physics. Any one of these barriers might be manageable, she said – a molehill, not a mountain. But these molehills pile up on one another, sometimes creating an impassable summit. The cumulative effect helps explain the enduring shortage of women in physics.

For science-loving girls, the path toward a career in physics steepens early on.

“Imagine a young girl starting out at school, saying ‘I love science and mathematics,’” Thomson said. “Immediately, she faces gender stereotypes, and bias that colours decisions – often without people realizing.”

Girls grow up with a shortage of women role models and mentors in physics. If they surmount that hill, they commonly face an uncomfortable and sexist workplace culture, early-career instability, bias against them in hiring and research grants, and being overlooked as conference speakers. They tend to get weaker reference letters than men with equivalent accomplishments.

The hills keep piling up – women are paid less than men, are underrepresented in prizes from the Nobel down, and tend not to be regarded as leaders no matter their accomplishments, expertise, or authority.

Not to mention that an aspiring academic’s prime career-establishing years, when they are expected to be at their most groundbreaking and productive, coincide with the years when many women are weighing the possibility of starting a family.

“There are still some really strange attitudes out there that going on maternity leave is like going on sabbatical. It isn’t,” Thomson said. Her own maternity leave was invaded by pressures that made it more challenging both to focus on being a new mother and to ensure her career stayed on track. “Your grad students don’t go away just because you’re on maternity leave. And you still have to stay competitive, you still have to apply for your next grant.”

For many women, the effort of running the obstacle course, of climbing hill after hill, of never being able to let their guard down, of being overlooked and under-remunerated, ultimately pushes them in a direction other than physics.

“These disadvantages compound over time,” she said.

Addressing systemic exclusion is a matter of human rights and social justice, Thomson said. But it’s also about improving physics.

“We need to reflect on what we reward,” she said. “Advancing EDI is one way you can address excellence in research. There’s a business case based on the need to foster excellence through the diversity of perspectives, and the scientific value of realizing human potential.”

Many academic institutions are increasingly investing in initiatives to change the gender balance – from Carleton’s creation of the dean position Thomson now holds, to Perimeter’s Emmy Noether initiatives – but Thomson pointed out that at the current rate of change, physics will get within 5 percent of gender parity 258 years from now. And that doesn’t factor in systemic exclusion of racialized people and other groups underrepresented in physics faculty and staff. A person who belongs to more than one of these groups finds the obstacles before them compounded and mutually reinforcing.

Thomson acknowledges that even people with a heartfelt desire to see circumstances change can be daunted by the complexity and magnitude of the issues.

“You don’t need to climb the whole mountain to change things,” she said. The slope can come down as it went up – piece by piece. “We need to have accessible, visible role models for students and trainees. Colleagues need to be empowered as allies, calling out discrimination. When it comes to implicit bias, people need to be self-aware and work to have humility, respect, and accountability.

“Hiring and granting committees need to adopt well-defined merit and evaluation criteria before they begin making decisions. Committee members have to work together to identify and mitigate each other’s bias. We are teaching the next generation of parents. If we incorporate the principles of EDI in our teaching, then they back react to gender bias.”

It’s a long list. But scientists, she reminded workshop participants, are no strangers to tackling big, complex challenges.

“Perimeter works on some of the hardest problems in theoretical physics. I work on treatments for cancer. We work on hard problems all the time,” she said. Taming the mountain is a matter of setting priorities, and staying the course.

“Let’s collaborate. We’ve got our list of things to do in physics. Let’s put equity, diversity, and inclusion at the top. Then you can do quantum gravity, grand unifying theory, whatever you want. Every physicist can be a part of this. We just need to keep going.”

Further exploration

About PI

Perimeter Institute is the world’s largest research hub devoted to theoretical physics. The independent Institute was founded in 1999 to foster breakthroughs in the fundamental understanding of our universe, from the smallest particles to the entire cosmos. Research at Perimeter is motivated by the understanding that fundamental science advances human knowledge and catalyzes innovation, and that today’s theoretical physics is tomorrow’s technology. Located in the Region of Waterloo, the not-for-profit Institute is a unique public-private endeavour, including the Governments of Ontario and Canada, that enables cutting-edge research, trains the next generation of scientific pioneers, and shares the power of physics through award-winning educational outreach and public engagement.

You might be interested in