Pi. 3.1415. π. The ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. It’s the world’s most famous irrational number and one that has fascinated mathematicians for millennia.

The 4000-year history of pi, and the long quest to find more of its digits, extends from ancient Babylon to the era of supercomputers. The story is almost as long as pi itself, and takes us from Mesopotamian granaries to American high schools, with a dozen twists and turns in between. Buckle up – we’re going back in time to see where the tastiest number in all of mathematics got its start.

3.14: The dawn of pi

Our story begins at the height of one of humanity’s first civilizations: ancient Babylon. An agricultural powerhouse built on the wealth of trade, Babylon was a place of commerce and change. Earlier Mesopotamian societies had shepherded in advancements like writing, numeric systems, and fancy new innovations like fractions. But Babylon’s tally-based numeric system and its invention of the abacus sped up calculations many-fold.

A more complex society required more complex math, and it was not long before a usable ratio for circles became a pressing need. It’s easier to tax your people, tally resources, and plan construction projects like cylindrical granaries if you have constants like pi.

The first records of pi date from about 2000 BCE. They show that Babylonians generally believed that pi was equal to three, but a clay tablet discovered in the 1930s showed that at least one ambitious person had figured out that pi was equal to about 25/8, or 3.3125.

Roughly 500 years later, in a different civilization alongside the mighty Nile River, an Egyptian scribe named Ahmes took the next big leap. A surviving papyrus, marked with dozens of calculations and math problems, gives us clues to the state of mathematics in Ahmes’ time. It shows that Egypt had made advancements in numerals and fractions in the intervening years, which helped Ahmes lay out pi as about 256/81, or 3.16.

The last major advancement from this early period emerged in India in about 800 BCE. Religious scholars were attempting to standardize the construction of altars that required different shapes (circles, semicircles, and squares) but take up the same area. They used ropes and bricks to “square the circle,” and, like the Babylonians, commonly referenced three – but their best approximations reached 3.138.

By this time, humanity hasn’t even invented the saddle, yet we have figured out pi to 1 percent accuracy. Pretty good!

3.1415: Squaring (and polygon-ing) the circle

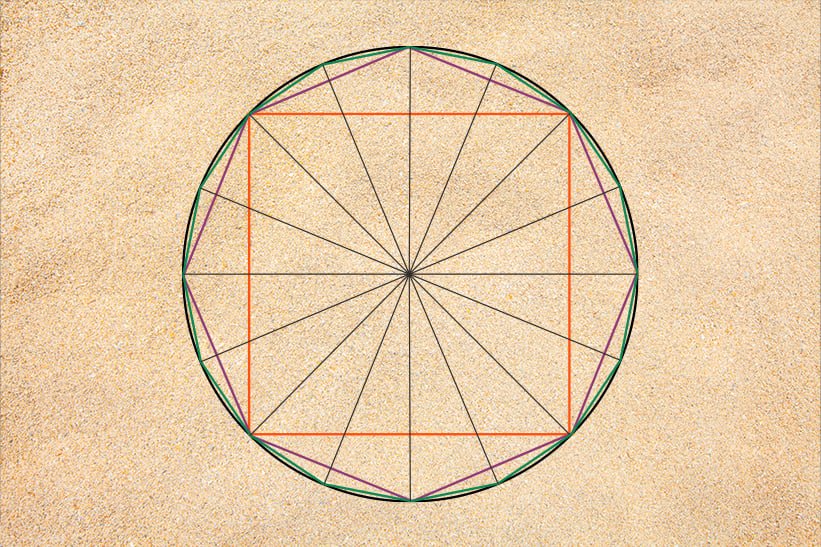

In Greece around 250 BCE, a mathematician named Archimedes figured out that a pentagon would be a better approximation for pi than a square, and a hexagon would be even better, and so on.

Archimedes’ approximation is called the ‘method of exhaustion’ because the measurements and calculations took a very long time. He started by drawing a circle and placing a square inside so the corners just touched the circle. Then, he drew a square outside the circle where the sides just touched the outside of the circle. If you add up the sides of each square and divide by a diagonal measurement of each, you get two numbers, between which is pi.

Archimedes then replaced the squares with pentagons and repeated the process. The numbers he calculated were even closer to pi. He doubled the sides of his polygons until he got to 96 sides and discovered that pi was somewhere between 3 1/7 (3.1429) and 3 10/71 (3.1408).

According to legend, Archimedes was still doing his circle calculations when his city was invaded by the Romans. His final words before being killed were apparently, “do not disturb my circles!”

Around the same time, Chinese mathematician Liu Hui came up with the first rigorous algorithm to calculate pi that took a little bit of the exhaustion out of the method of exhaustion. Like Archimedes, Liu Hui used polygons to calculate pi. In his method, he put a hexagon inside of the circle (see diagram), cut the hexagon in half, and sliced it further into a series of triangles. From there, he used Pythagorean theorem – repeatedly – to create more triangles, which could be used to calculate a closer approximation. Using this iterative algorithm, Hui eventually reached an estimate of pi to five digits, or 3.1416.

Hui concluded that 3.14 was a close enough estimate for most purposes. Other Chinese mathematicians disagreed. Two hundred years later, Zu Chongzhi used the method to calculate pi between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927, a record that held for centuries afterwards.

The next major innovation in pi’s history didn’t add new digits, but it did make the calculations more efficient. A 6th century CE mathematician, astronomer and early physicist named Aryabhata, born in India, concluded, “Add four to 100, multiply by eight, and then add 62,000. By this rule the circumference of a circle with a diameter of 20,000 can be approached.” Essentially 62832/20000, or 3.1416.

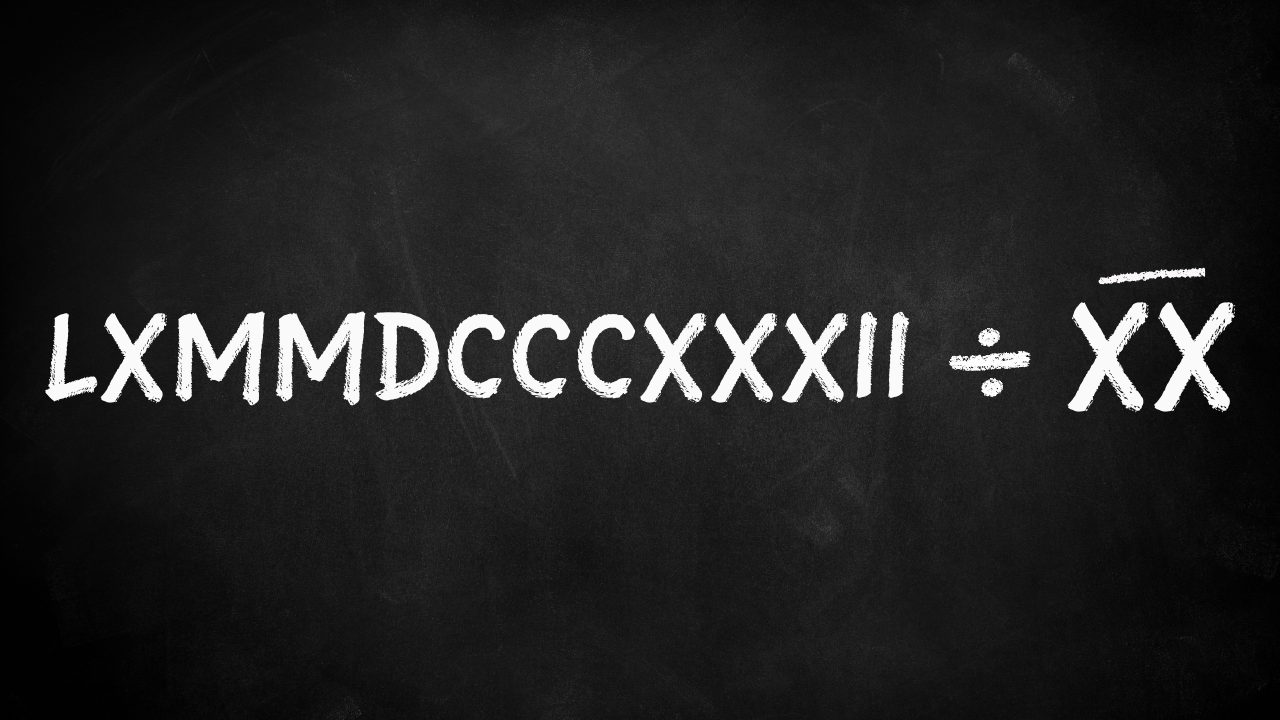

While we’re not sure how Aryabhata came to these numbers, we do know that they used a place value numeric system, which assigns values to digits based on their position in a number (like how 30 means three groups of 10). This makes calculations much faster. Imagine trying to do 62832/20000 using only Roman numerals. For the record, that would be:

3.14159265359: pi takes off

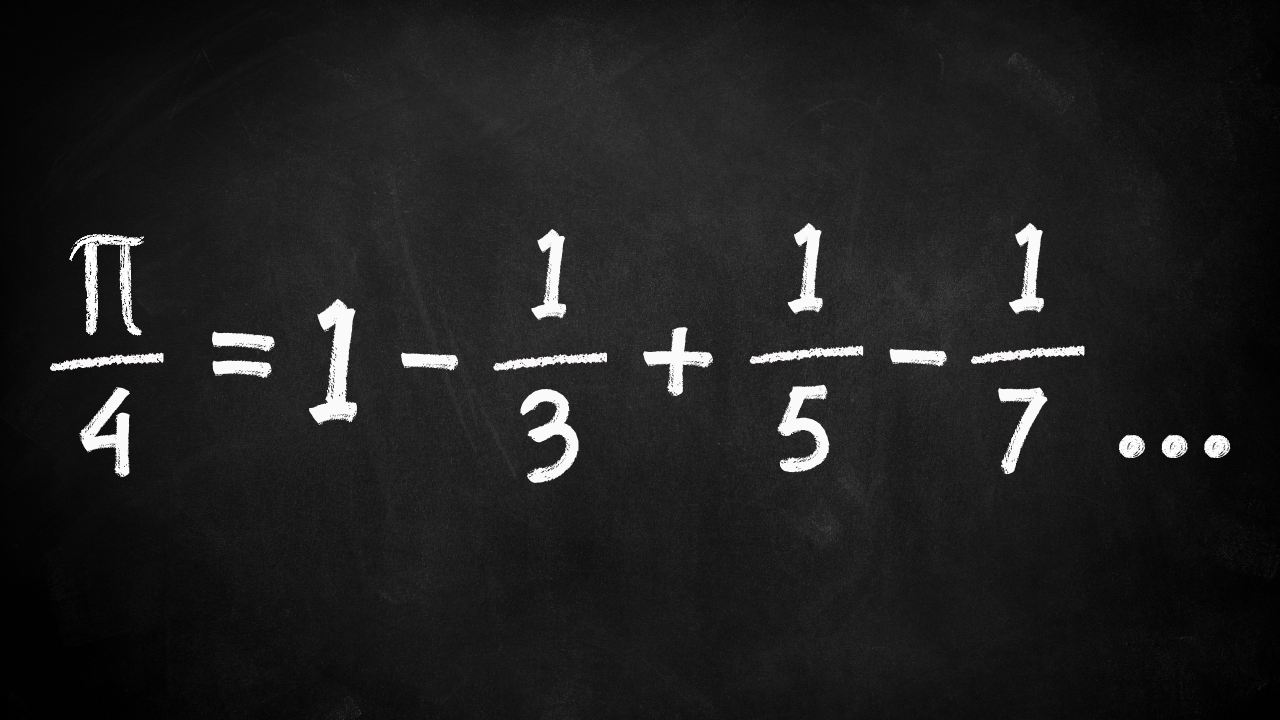

Pi remained relatively unchanged for some 700 years, until another Indian mathematician named Madhava of Sangamagrama unlocked more digits, using the power of infinite series.

Not much is known about Madhava. He was born around 1340 CE, and what we know about him and his teachings comes from the writings of his students. Among Madhava’s many innovations in math were his use of infinite series approximations for different trigonometric functions.

Madhava realized that by successively adding and subtracting different odd number fractions, a much better estimation of pi was possible. It looked like this:

Madhava also came up with a correction that helped him calculate pi to the 11th decimal point, or 3.14159265358. The series would be rediscovered 300 years later in Europe and named the Leibniz formula. But today many refer to it as the Madhava-Leibniz formula to honour Madhava’s important contribution.

The next major leap came just a century later, from Persian mathematician Jamshid al-Kashi in 1424. He references Archimedes in his work and seems to have taken the method of exhaustion to new heights. But armed with a better numeric system and advancements in fractions, Al-Kashi determined pi to a record 16 decimal points, or 3.14159265358979323.

Infinite series finally hit Europe in 1593, when François Viète published the first such formula in European mathematics. During the next 300 years, Europeans came up with even more digits using infinite series and increasingly efficient ways of calculating Archimedes’ method of exhaustion.

In 1654, Christiaan Huygens used what would eventually be called the Richardson Extrapolation to shorten the inequalities in Archimedes’ method. He used the centre of gravity in a segment of a parabola and applied that to circles, leading to faster and more accurate approximations.

From there, pi exploded. In the 1670s, James Gregory and Gottfried Leibniz both used the Madhava-Leibniz series to calculate pi to even more digits. In 1706, John Machin got to the first 100 decimal places using a variation of Madhava-Leibniz combined with the Taylor series expansion (named after Brook Taylor but discovered by Madhava in the 1300s).

That same year, a close friend of Isaac Newton named William Jones started using the symbol π to represent pi, which was a shorter representation of Greek word periphery (περιφέρεια). In the 1760s, Johann Heinrich Lambert proved that pi is an irrational number.

Despite increased efficiencies, the process was arduous and susceptible to human errors. For example, William Rutherford calculated 208 digits of pi in the 1800s, but only 152 were correct. William Shanks got all the way to 707 digits in 1873, but only the first 527 were correct. Regardless of their errors, mathematicians were now calculating pi to hundreds of digits.

An invention was coming, however, one that would take pi from hundreds of digits to trillions.

The computer.

To 3.1415926535897932384626433832795028841 and beyond

Once the computer was invented, the race entered warp speed and hit trillions of digits in less than 80 years.

That’s probably more than we’ll ever need. To put that many decimal points in perspective, you can use pi to the 38th digit to calculate a circle the size of the universe and be accurate to the size of a hydrogen atom, according to Marc Rayman, Chief Engineer for Mission Operations and Science at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab. But practicality hasn’t stopped mathematicians and computer scientists from pushing the envelope.

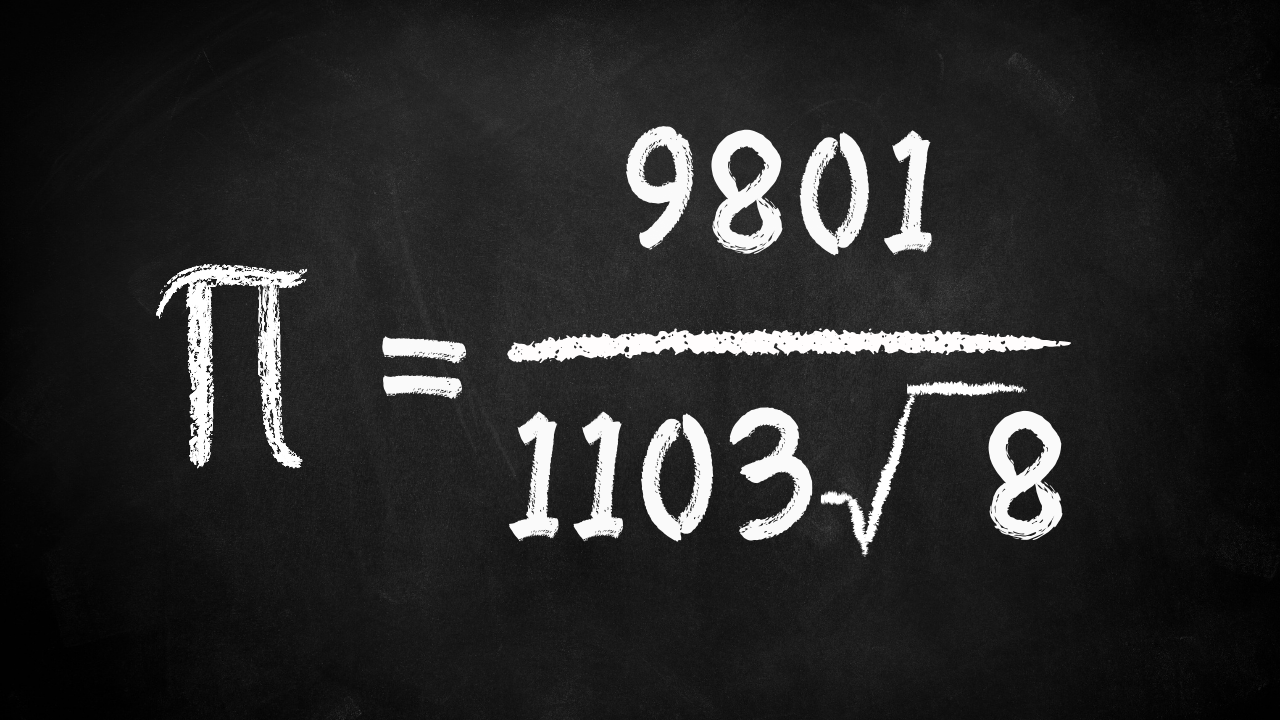

The current method for calculating new digits of pi relies on the work of Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, born in 1887. Working with infinite series, Ramanujan came across a few instances that converged together for a much more efficient calculation:

Ramanujan never explained how he came up with this calculation, including using 9801 and 1103, but the formula is incredibly efficient. It takes only one term to calculate six decimal places. The Madhava-Leibniz series needs over 1.4 million terms to get to the same place.

Ramanujan’s series has been the basis for all the fastest computer algorithms computing new digits of π in the last half-century. In 1988, the Chudnovsky brothers published an algorithm based on Ramanujan’s formula to calculate pi to the billionth decimal place. Since then, Japanese collaborators Yasumasa Kanada and Daisuke Takahashi set 11 of the past 21 pi records using this algorithm.

The latest major innovation in pi is called y-cruncher, a software created by American developer Alexander Lee based on work he began in high school. While originally developed to calculate the Euler-Mascheroni constant, it has been used in every record-breaking calculation of pi since, up to the most recent: Jordan Ranous, Kevin O’Brien and Brian Beeler in June 2024, where they calculated the 202,112,290,000,000th digit of pi (it’s a 2, if you’re curious).

Why pi?

At this point, we have more digits than we know what to do with. Pi to the 202 trillionth digit may not be practical for calculating circles, but it is useful in computer science. First, calculating pi is a great benchmark for understanding computational power. And the seemingly random and even distribution of digits makes pi an excellent random number generator. But even then, 200 trillion seems excessive.

So why do this? Perhaps Youtuber Simon Clark said it best: “Humans are weird. We like to understand the world around us and, as our civilization has developed, we’ve built increasingly complex tools to help us understand. It wasn’t essential to our survival… we just did it because that’s the way we’re wired.”

From the first estimates using simple tallies, through the construction of altars and granaries, to the limits of today’s software algorithms, pi remains something we can forever discover more of. It’s almost a challenge, built into nature itself: “I dare you…if you can.”

About PI

Perimeter Institute is the world’s largest research hub devoted to theoretical physics. The independent Institute was founded in 1999 to foster breakthroughs in the fundamental understanding of our universe, from the smallest particles to the entire cosmos. Research at Perimeter is motivated by the understanding that fundamental science advances human knowledge and catalyzes innovation, and that today’s theoretical physics is tomorrow’s technology. Located in the Region of Waterloo, the not-for-profit Institute is a unique public-private endeavour, including the Governments of Ontario and Canada, that enables cutting-edge research, trains the next generation of scientific pioneers, and shares the power of physics through award-winning educational outreach and public engagement.