Brilliant women are everywhere. Unfortunately, their stories often aren’t. To celebrate International Women’s Day 2019, Perimeter Institute is releasing three more “Forces of Nature” posters recognizing the indelible contributions of pioneering women scientists.

Scientists previously featured in the free, downloadable series include Nobel winners Donna Strickland and Marie Curie, as well as Vera Rubin, Chien-Shiung Wu, Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Ada Lovelace, and more. Today, those greats are joined by three more.

Maria Goeppert Mayer

Download the printable high-res poster

German-born Maria Goeppert Mayer had her sights set on a research career from childhood. She knew what it entailed: her family included six generations of university professors. She would become the seventh, but the path wasn’t easy.

After receiving her PhD at Göttingen and moving to the USA with her American physicist husband, Joseph Mayer, no universities were willing to hire her. Some even cited nepotism rules to avoid having a woman professor on staff. Still, Goeppert Mayer continued to do physics “for fun” until the couple reached Chicago in 1946, where she was appointed a professor at the Institute for Nuclear Studies and worked at the Argonne National Laboratory.

It was known at the time that an atom consisted of a nucleus surrounded by “shells” of electrons at different energy levels. In 1949, Goeppert Mayer developed a model for the nucleus itself, in which nucleons inside the nucleus were distributed in shells with different energy levels. Another researcher, Hans Jensen, came to a similar conclusion around the same time. The two researchers shared the 1963 Nobel Prize – making Goeppert Mayer the second woman in history to win the award. (The San Diego Tribune ran the story under the headline “S.D. Mother Wins Nobel Physics Prize”.)

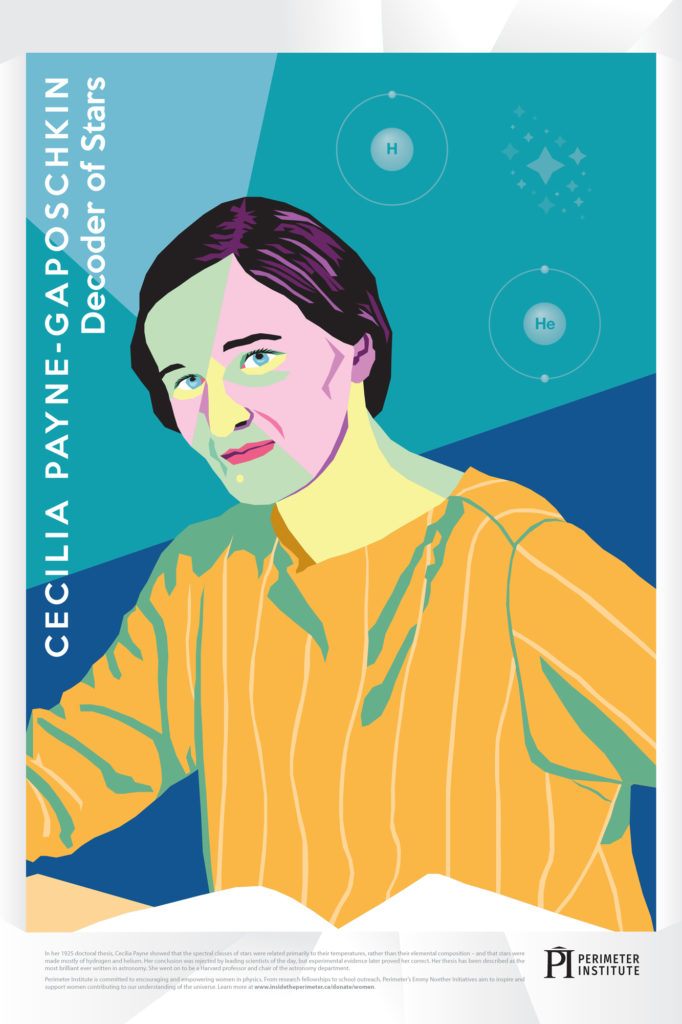

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

Download the printable high-res poster

When British-born Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was a science student at Cambridge University, she happened to get tickets to a talk by Arthur Eddington about his groundbreaking 1919 expedition to Principe during a solar eclipse that gathered evidence in support of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The lecture changed her life, and she fixed her sights on astronomy. But her only career option in the UK was teaching, so she left for the US in 1923.

When Payne-Gaposchkin wrote her doctoral thesis at Harvard in 1925, her findings went against the day’s leading scientific theories. Consensus at the time was that stars had generally the same composition as the Earth. Payne-Gaposchkin proposed something wildly different: that they were made mostly of hydrogen and helium, and could be classified according to their temperatures.

Leading scientists rejected her idea, but experimental evidence eventually proved her correct. In the 1962 book Astronomy of the 20th Century, Otto Struve and Velta Zebergs deemed her work “undoubtedly the most brilliant PhD thesis ever written in astronomy.”

While her career was hampered by sexism (while she was allowed to teach at Harvard, those courses weren’t actually listed in the university catalogue), in 1956 she was appointed as a Harvard professor and chair of the astronomy department. She held both positions until her retirement 10 years later.

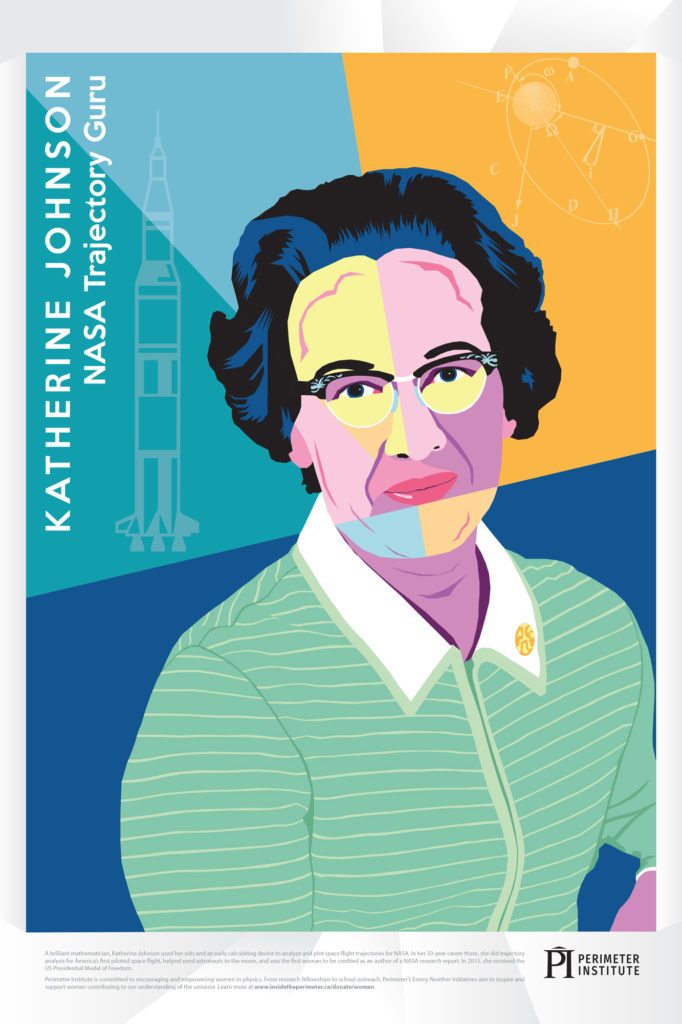

Katherine Johnson

Download the printable high-res poster

Katherine Johnson’s mathematical brilliance was clear from a young age. The problem was, local schools in her West Virginia hometown did not offer education past eighth grade for African-Americans. So her parents enrolled their four children in a high school on the campus of the historically black West Virginia State College. Katherine graduated at the age of 14. By 18, she had earned a double degree in mathematics and French. In 1939, Johnson was one of three black students to integrate the state’s graduate schools, but she left her studies a year later to raise a family.

Johnson became a teacher, working in West Virginia’s segregated schools for more than 10 years until, in 1952, one of her relatives mentioned that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics – the precursor to NASA – was hiring mathematicians. She applied, and the following year, at age 34, she was hired as a “computer.” Again, her brilliance quickly revealed itself, and Johnson was assigned to Langley’s flight research division.

In her 33-year career at NASA, Johnson did trajectory analysis for America’s first piloted space flight, helped send astronauts to the moon, and was the first woman to be credited as an author of a NASA research report. Her story was documented in the book and film Hidden Figures, and in 2015 she was awarded the US Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

** Download the entire series here for free. **

About PI

Perimeter Institute is the world’s largest research hub devoted to theoretical physics. The independent Institute was founded in 1999 to foster breakthroughs in the fundamental understanding of our universe, from the smallest particles to the entire cosmos. Research at Perimeter is motivated by the understanding that fundamental science advances human knowledge and catalyzes innovation, and that today’s theoretical physics is tomorrow’s technology. Located in the Region of Waterloo, the not-for-profit Institute is a unique public-private endeavour, including the Governments of Ontario and Canada, that enables cutting-edge research, trains the next generation of scientific pioneers, and shares the power of physics through award-winning educational outreach and public engagement.

You might be interested in