Is nature a computer?

This is an interesting question, and the answer depends, in part, on what you mean by a computer.

If you are thinking about your laptop, then the idea that nature is a computer is a bit of stretch, both scientifically, and philosophically since it would raise the dicey question of who or what built it.

But if you are thinking about computation in the loose sense of a system that processes information according to a set of rules, then some scientists would say that nature does fundamentally operate as a computational system.

In a regular laptop, or what quantum information scientists call a “classical computer,” the computations are essentially just down to electrical signals that go through a gate mechanism or not, translated into “bits” of zeros and ones.

Even a mind-bogglingly powerful supercomputer like El Capitan, at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which is capable of 2.79 exaflops, or 2.79 quintillion calculations per second, is really a linear calculating machine. It is still based on electrical signals that go through gates, or not, translating into strings of zeros and ones like 01000101 ….

But today we have access to quantum mechanical gifts of nature that allow us to make quantum computers that could be much more powerful than classical computers, or supercomputers.

One of those quantum mechanical gifts of nature is superposition. Another is entanglement.

Superposition means that a particle can be in two states at the same time. This is a counter-intuitive feature, and we don’t have an equivalent in our macroscopic world. But, for example, an electron, can be in a state of both spin up and spin down states at the same time. (A spin is like the intrinsic angular momentum of the field the electron occupies).

In quantum computing, this superposed unit of a two-level state is called a qubit. It can be translated as both zero and one at the same time. Each superposed qubit is a like a package containing much more information than what a mere bit can carry.

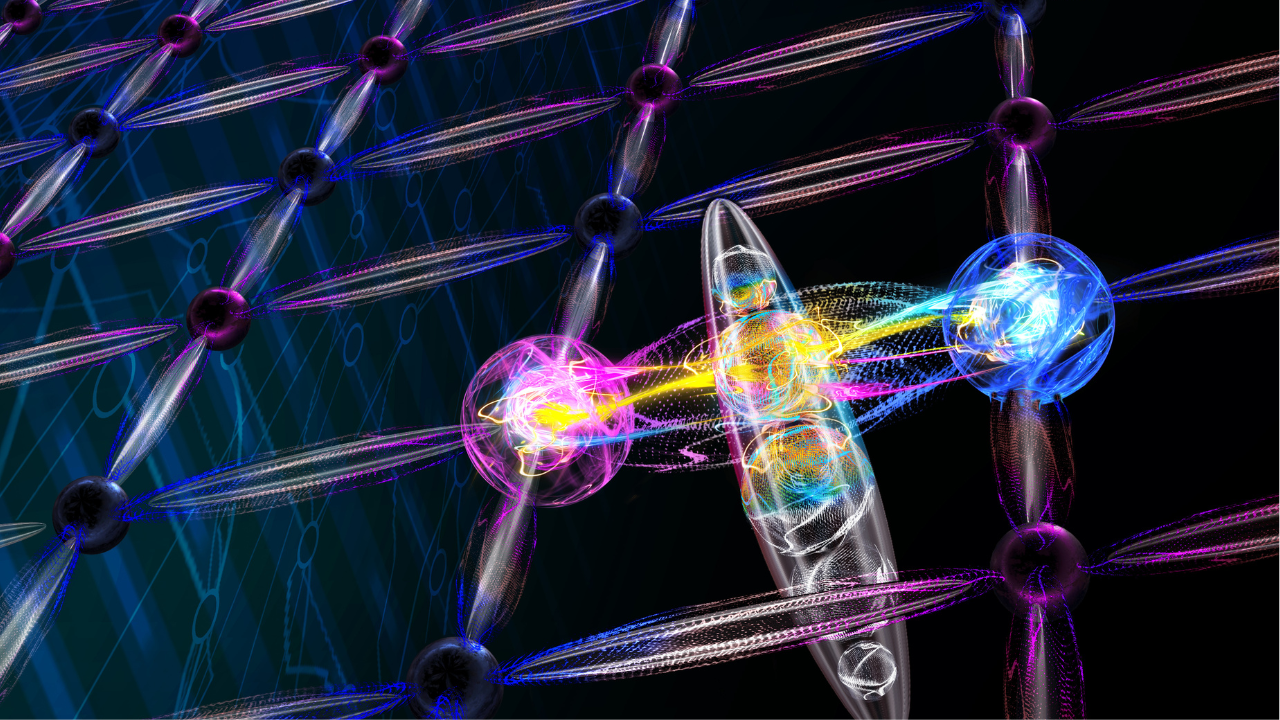

The other quantum mechanical gift of nature, entanglement, is the strong correlation between particles at great distances. It too is counter-intuitive and was famously derided by Albert Einstein as “spooky action at a distance.” But today, entangled particles can be made in a lab, and this quantum mechanical gift of nature can be also used in quantum computing. Entanglement allows quantum computers to manipulate many qubits in a single operation and can be used to implement various protocols and algorithms that are not possible in regular computers.

But even the superposed and entangled qubits are still binary – and nature is not so binary.

In an atom, for example, electrons can occupy many different energy levels, depending on the amount of energy in the system. And although electrons always come in spins of one-half, there are other types of particles – like the W and Z bosons – that have more than two spin states.

Going beyond the binary and accessing these multi-level states of different particles could make quantum computing more efficient and therefore more powerful.

Christine Muschik, a research associate faculty member at Perimeter and a professor at the University of Waterloo Institute for Quantum Computing who heads the quantum interactions theory group, is going beyond qubits, into this multi-level realm of qudits.

She hopes this can help solve some of the challenges faced in quantum computing.

Quantum computers do exist today. Many institutions and large companies such as Google, IBM, and Microsoft, as well as smaller players, have been building them.

But the big challenge is the lack of control. The biggest problem is known as quantum decoherence, and it refers to the process where anything that disturbs the particles will cause them to lose their special quantum mechanical gifts. There are quantum error correcting codes that make quantum computing possible today on a small scale, but even so, these systems are very error prone. This is one of the reasons that large, practical quantum computers have been so difficult to build.

Muschik hopes her work with qudits will make it easier. She is one of two co-leads in a recent paper in Nature Physics, “Simulating 2D lattice gauge theories on a qudit quantum computer.” This recent paper follows another paper, Simulating 2D Effects in Lattice Gauge Theories on a Quantum Computer that she led and was published in the open access journal PRX Quantum in 2021.

Working out the complex interactions of particles and forces involves gauge theories that form the backbone of the Standard Model of particle physics. Gauge theories are used, for example, in quantum chromodynamics (QCD) that won the Nobel Prize in 2004. This theory describes the strong force interactions of quarks that are mediated by gauge gluons in the nuclei of atoms. Gauge theories are also used in describing the interactions between charged particles with the electromagnetic forces mediated by gauge photons.

But these interactions at the heart of nature are extremely complex and dynamic. They are difficult to work out, even using supercomputers. Ultimately, one would love to be able to be able to work out everything that is happening in a Hilbert space which is the mathematical space that contains all possible quantum states or vectors that the quantum particle might be in. But this has been notoriously difficult for computers to achieve.

Muschik thinks that qudits can get us closer to her dream of simulating quantum physics using a quantum computer.

The “d” in qudit stands for dimensions. These are units representing the higher-level Hilbert spaces. Instead of a qubit in two possible states (0 and 1), a qudit can exist in d possible states. It can be a qutrit (d=3) in three possible states: 0, 1, and 2. Or, it can be a ququart (d=4) in four possible states: 0, 1, 2, and three. Or a ququint, (d=5) in five possible states: 0,1,2,3,4.

Qudits can go up from there, to any number of levels.

“One of the most interesting aspects about our qudit work is that almost all quantum systems can be in more than two states. That's in fact very natural for quantum systems,” Muschik says.

“Take atoms (or ions) as an example: usually researchers pick two different states, which they call 0, and 1. However, almost all atoms have many different states. But you could pick three energy states in your atom and voilà! You have a qutrit. Or if you feel confident enough that you can control five levels, you can have a ququint,” Muschik says.

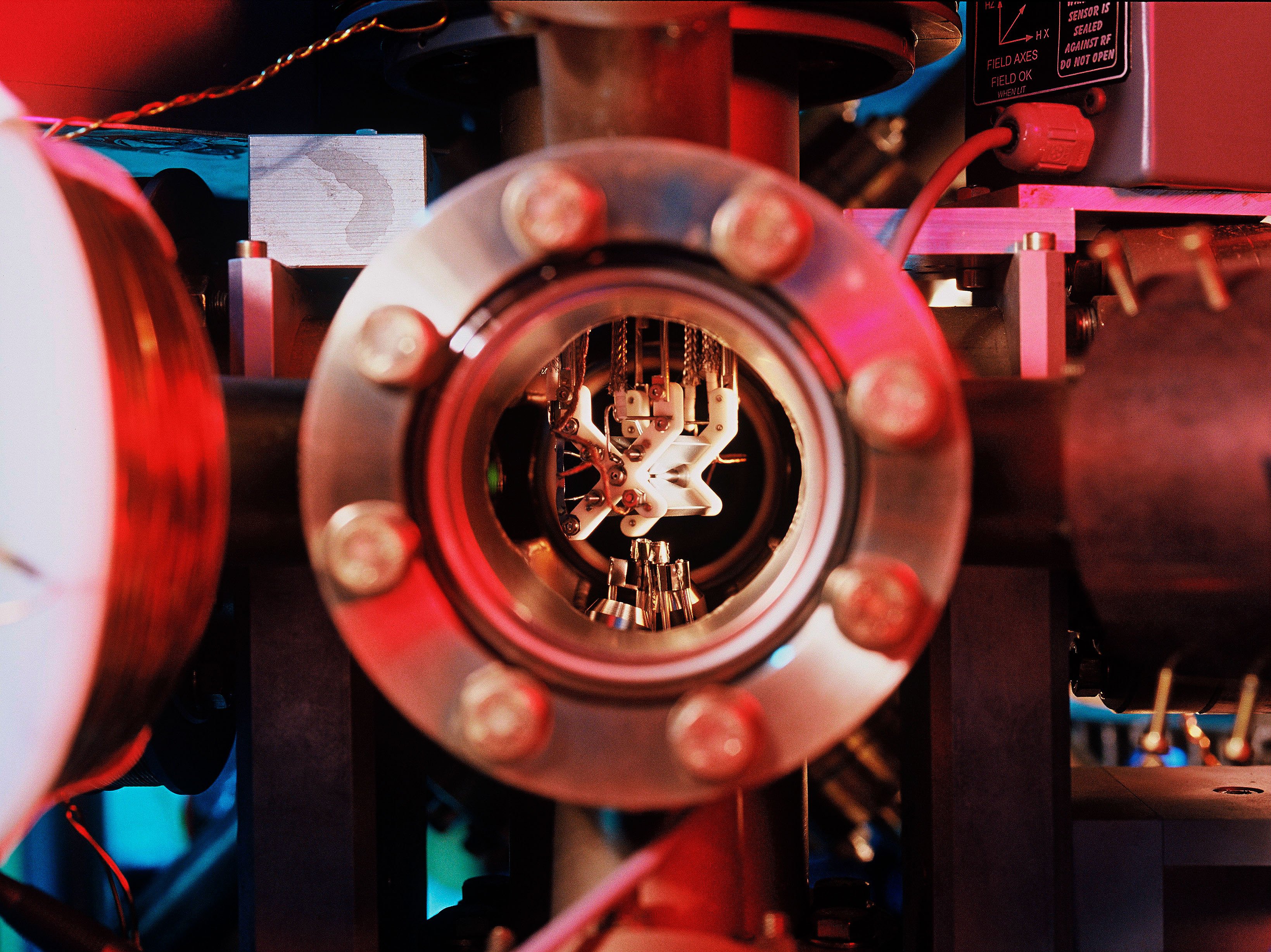

There are various ways of physically making these qudits. Muschik’s theory team has been working with an experimental group at the University of Innsbruck in western Austria using a trapped ion quantum computer that manipulates calcium ions (charged calcium atoms).

Calcium ions naturally have multiple accessible energy states, and these ions can be trapped using electromagnetic fields and manipulated with lasers to create a formidable quantum computing system.

Much like your regular computer has logic gates, which are like switches that turn off, or on, forming the building blocks for digital circuits, the quantum computers have quantum gates, which are quantum circuits using small numbers of qubits.

Muschik says that using the alternative to qubits – the qudits – allows a quantum computer to do more with less, and thus reduce the errors.

“A complex problem solved with qubits requires a long circuit with numerous quantum gates. However, in the current era of noisy and imperfect gates, excessive gate operations lead to significant error accumulation. By reducing the number of gates, errors decrease, yielding cleaner results. Using qudits instead of qubits enables more efficient and therefore shorter circuits that yield improved outcomes,” Muschik says.

Muschik says that beyond just being able to use quantum resources more efficiently, there are other advantages to using qudits that are still being explored. “There is the big field of quantum error correction. With qudits, we could find ways of correcting errors that are not possible just using qubits,” she says. “You could also have a lot more freedom in creating the quantum entangled gates, but this too is still under-explored.”

In most experiments in the past, researchers have simply chosen to ignore all but two states. With superconducting quantum systems, such as those used by companies such as Google or IBM, for example, researchers have in fact traditionally gone to great lengths to artificially reduce the system to only two states, ignoring all the others. That is mainly because “it only helps you to have more levels if you can also control them,” Muschik says. “If you have fewer levels, you basically have an easier time controlling everything.”

Inside the Quantum Interactions group: Christine Muschik and her team are exploring the power of qudits to simulate complex particle interactions and push quantum computing beyond binary. Video credit: Kindea Labs / Watch on YouTube

What changed is that in recent years, the University of Innsbruck researchers have been able to develop high quality qudit gates that are of the same fidelity as qubit gates, Muschik says. “They have a new approach to making qudit gates that are really nice and high quality. So, we can now start to use this richness instead of ignoring it,” she adds.

“The experimental team at Innsbruck built the qudit quantum computer, and my theory team in Waterloo developed the qudit protocol that allows one to simulate fundamental particle interactions on this new device. Together we did a quantum simulation, a quantum calculation, which is running our protocol with their qudits.”

The recent experiment described in Nature Physics demonstrated that the qudit gates are a big improvement over the traditional qubit approach. Moreover, the researchers demonstrated a crucial step on the path toward being able to use gauge theories to simulate the interactions in nature. It is the first time that a full-fledged qudit algorithm has run a quantum computer, Muschik says. “We are proud of that.”

Muschik says her team has been working on qudits for about five years.

“Initially, like everyone else, I worked with qubits. My goal was to simulate fundamental particle interactions—an extremely challenging task, even for quantum computers. After two and a half years of struggle, we were on the verge of giving up due to hardware limitations. Then, we connected with an experimental ion-trapping group in Austria pioneering qudits. Collaborating with them, we successfully ran our quantum simulation using their qudits.”

Many other quantum computing groups are also highly interested in working with qudits, Muschik says. "We may well be at the beginning of a new wave in quantum information processing."

She says her primary reason for doing this is to understand particle interactions in nature. “We want to develop quantum protocols to help us to understand the Standard Model of particle physics and the universe around us. We hope that future quantum computers will help us to study what happens inside a neutron star or in dynamical particle-antiparticle creation.” she says. “However, quantum technologies more broadly can benefit from using qudits: this is a very hard-ware efficient approach for all types of quantum computations, for new protocols in quantum communication and for quantum sensing.”

She is enormously excited about what the future holds in this new realm of quantum computing using qudits. “This is still a young field. My team and I feel like pioneers,” she says.

About PI

Perimeter Institute is the world’s largest research hub devoted to theoretical physics. The independent Institute was founded in 1999 to foster breakthroughs in the fundamental understanding of our universe, from the smallest particles to the entire cosmos. Research at Perimeter is motivated by the understanding that fundamental science advances human knowledge and catalyzes innovation, and that today’s theoretical physics is tomorrow’s technology. Located in the Region of Waterloo, the not-for-profit Institute is a unique public-private endeavour, including the Governments of Ontario and Canada, that enables cutting-edge research, trains the next generation of scientific pioneers, and shares the power of physics through award-winning educational outreach and public engagement.