What tools do you need to learn quantum mechanics? A few rubber bands, two pencils, and a small laser will do the trick.

That’s how participants in this year’s International Summer School for Young Physicists (ISSYP) got their introduction to the topic, learning how light can act as both a particle and a wave.

ISSYP’s two-week online program is full of hands-on activities that bring physics concepts to life, each followed up with an explanation of the mathematics that underlie the demonstrations. There is even optional material that gives students the opportunity to go as far down the physics rabbit hole as they desire.

“That’s what’s great about this program,” says Shaya Farahmand, a high school student from Upper Canada College in Toronto. “It basically allows us to focus on the concepts that we’re interested in and go deeper on them and develop more of an understanding about them.”

ISSYP has been running for more than two decades, helping high school students across Canada and around the world to level up their understanding of fundamental physics. This year, 44 students attended: 23 Canadians and 21 international students representing 13 countries. More than half the participants identified as women or gender diverse.

The program has been run online each summer since 2020, and ISSYP’s organizers seek to create a unique, close-knit community among its participants. Students help each other learn, and they begin to form what might some day become a long-term peer network.

“The people here are extremely supportive,” says Farahmand of his classmates. “We’re all learning together, and are always willing to answer questions, help out, and engage in discussion. We’re sharing our observations, sharing our findings, and it’s through this discussion that we all learn more.”

Antonia Macha, one of Farahmand’s peers attending from Germany, agrees.

“The people are great. Usually in online classes, people are really, really inactive. Everyone just turns the camera off and goes into their own work, which can be really frustrating. Here, I did not have this experience. Everyone is talking and interacting, and you can actually discuss the problems. I really get the feeling that I’m meeting a lot of new people which I’m going to stay in contact with even after the program.”

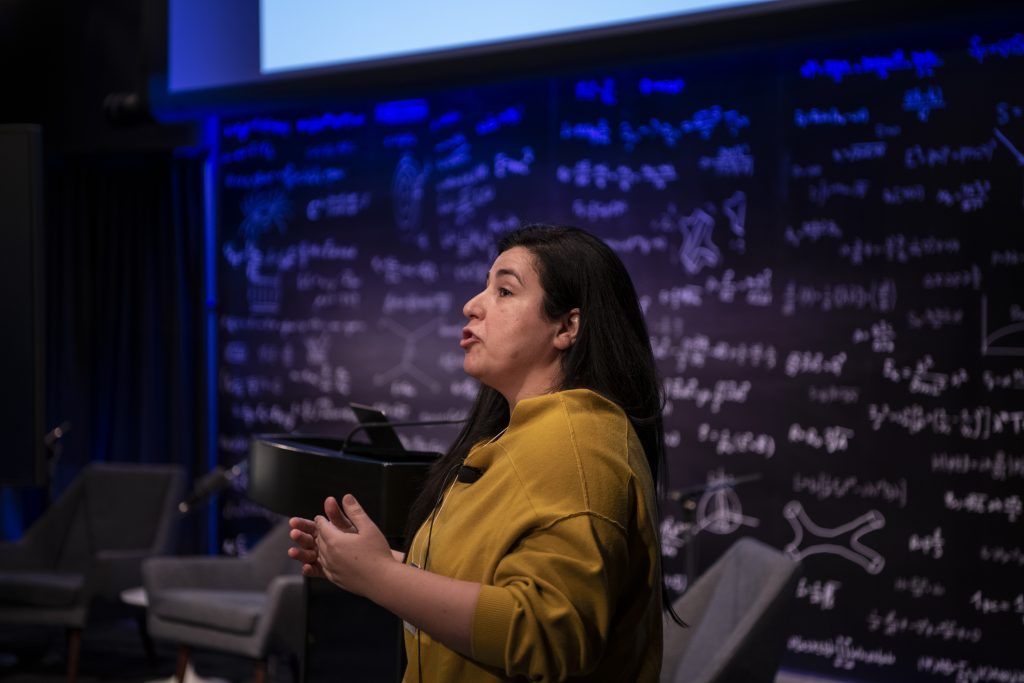

Some of the highlights included the chance to ask questions of Latham Boyle, now a Perimeter Visiting Fellow from the University of Edinburgh, and Perimeter Faculty member Asimina Arvanitaki, both leading minds in their respective fields who gave keynote talks at ISSYP this year.

Students also spent a week working with mentors, taking a deep dive into some fundamental areas of physics. Macha, for example, worked with Perimeter Scholars International Fellow Bindiya Arora and associate graduate student Vipul Badhan to learn about quantum gates, a core part of quantum computing. Farahmand, meanwhile, worked with Perimeter Research Scientist Elie Wolfe to learn more about Bell’s theorem, an important piece of the underlying physics behind quantum entanglement.

“I find the mentorship sessions to be very valuable,” says Farahmand, “because I can gain some insight on some of the research that people at Perimeter are working on right now. Learning about Bell’s theorem is really good, because I’m very interested in quantum computing and quantum information theory. It’s just very valuable experience.”

The part of ISSYP that stood out most for Farahmand was an experimental design activity where they built a magneto-hydrodynamic propulsion system.

“Essentially, it uses magnetic fields and electric fields to propel objects in water. So we had to make a system and also investigate the variables that affect the speed of the water. That was very fun. It helped us to understand how scientists think, and it was pretty cool to get hands on with the sort of physics that we look at theoretically and see how we can apply it.”

Finding practical applications for theoretical physics is right up Farahmand’s alley. He plans to study computer science and to eventually put emerging technology like artificial intelligence and quantum computing to use to solve real world challenges.

“It’s not just about the technology, but it’s also about the problems the technology can solve. What matters is finding tools to solve these problems. And these tools take the form of emerging tech,” says Farahmand.

Macha’s own approach to theoretical physics is built on the same foundation of curiosity and problem solving, but for her, it is more about discovering fundamental insights into how our universe works. The joy of discovery kept her motivated – and that’s a good thing, because some of the sessions were in the middle of the night for her since she was participating in ISSYP from Germany. Despite the time difference, Macha felt she was able to grapple with hard topics and make real progress in her understanding.

“We had a session on Hawking radiation that was really, really interesting,” she says. “I knew before that it was something to do with a particle/anti-particle pair suddenly appearing out of space, and then one being sucked into a black hole. But prior to today, I didn’t really understand how this fully works. Today was really great: I had a moment of ‘Yeah! Okay! That’s making a lot of sense now.’”

Macha was inspired to apply for ISSYP after learning that Perimeter was home to one of her academic role models, Katie Mack. And the summer school program is only the start of Macha’s physics career. She will be studying math and physics at Humboldt University in Berlin starting this fall.

So what is it about theoretical physics that Macha finds so compelling?

“I really like that you’re able to just look at phenomena and then try to explain them qualitatively, but also quantitatively. You start by building a model, and you can actually test it out in real life,” says Macha. “You test it experimentally, and then you can adjust your model and make it even better.”

Farahmand, Macha, and their peers celebrated the end of their two weeks of discovery with a closing ceremony, where they presented the results of their mentoring sessions and reflected on what they’d achieved.

Kelly Foyle, Perimeter outreach scientist and one of the organizers of ISSYP, made it clear that this was a beginning, not an end, to their journey of discovery: “It’s sad to see these two weeks come to a close, but I’m excited to welcome you today into a community of young physicists that have come through the ISSYP program. You’re joining a group of 900 alumni from 60 different countries,” she said.

Darcy Krahn, community manager at RBC Waterloo, also joined the closing ceremonies to celebrate with the students. ISSYP has been supported by RBC’s Future Launch program for more than a decade.

“ISSYP has launched hundreds of budding youth scientists on to advanced learning and promising careers,” Krahn told the students. “You have gathered this week from across Canada and the rest of this world. And to see such a diverse group of talented young people who will be shaping the future of theoretical physics is a true privilege of mine.”

Krahn praised their accomplishments over the course of the two-week program, expressing how excited he was to see where their futures might take them.

“You worked alongside some of the most brilliant minds, built up your peer and professional networks, advanced your STEM education, challenged your thinking, and developed skills like critical thinking and collaboration, all of which will help you take the next step forward in your career journeys. I know our future is very bright, with brilliant diverse minds like each of you leading the way. A sincere congratulations to each one of you. You have accomplished so much, and should be extremely proud,” he said.

Wherever Farahmand, Macha, and their 42 peers from around the world end up, their journeys are sure to be exciting. Physics taps into something primal in humans – a desire to learn and understand and discover. For this year’s young physicists, ISSYP was a first step on that voyage of discovery.

“Our universe has so many different phenomena, and all physics is doing is just trying to develop models that will help us explain it,” says Farahmand. “Really, the thing that excites me the most about physics is that it’s researcher initiated. Essentially, it all starts with a question and an observation by someone, and that’s what initiates our curiosity that allows us to come up with experiments, or develop models, or reflect on observations. It really taps into our curiosity in order to find explanations for the phenomena that we observe.”

ISSYP is funded by the RBC Foundation in support of RBC Future Launch.

About PI

Perimeter Institute is the world’s largest research hub devoted to theoretical physics. The independent Institute was founded in 1999 to foster breakthroughs in the fundamental understanding of our universe, from the smallest particles to the entire cosmos. Research at Perimeter is motivated by the understanding that fundamental science advances human knowledge and catalyzes innovation, and that today’s theoretical physics is tomorrow’s technology. Located in the Region of Waterloo, the not-for-profit Institute is a unique public-private endeavour, including the Governments of Ontario and Canada, that enables cutting-edge research, trains the next generation of scientific pioneers, and shares the power of physics through award-winning educational outreach and public engagement.

You might be interested in